‘The Great Rift’ Review: From Comity to Culture War

Math-based science was long guided by notions of the real world established by philosophy and theology. A rift now divides these realms. David J. Davis reviews “The Great Rift” by Michael E. Hobart.

By

David J. Davis

Science and religion have hit a rough patch. Like a married couple whose kids have moved out, the balance in the household has been lost and neither is entirely sure of the other. Should religion adapt its narratives to scientific explanations? Should science submit to the moral truths of religion? Should they operate in Stephen Jay Gould’s “non-overlapping magisteria”—separate realms of inquiry that ignore each other completely?

For roughly two millennia, these questions did not need asking. Both the classical and medieval worlds had their own balances, where science and religion inhabited the same intellectual space, offering together a holistic image of reality. Beginning in the 17th and 18th centuries, however, the balance slowly dissolved. Arguments over planetary motion, human evolution and the origins of the universe escalated into full-scale culture wars. Preferring divorce to continued discord, the modern banner-men of these wars argue, as the biologist Richard Dawkins has done, that “not only is science corrosive to religion, religion is corrosive to science.”

“The Great Rift” provides some historical context for the origins of this discord. While Mr. Dawkins almost relishes the conflict, Michael Hobart is more ambivalent about it but no less resolute in his belief that “neither science nor religion can bridge the gap.” In a sweeping history from ancient Greece to the 17th century, he locates the source of the rift in the different information technologies that science and religion employ. Building upon Gould’s principle of non-overlapping realms, Mr. Hobart argues that, since Galileo (1564-1642), science has communicated in abstract numeracy, while religion remains anchored in logos, “the logic coupling words and things.” Not only can the two realms not communicate with each other, he says, but numeracy has proved to be better at grasping reality. Holding up the elegant simplicity of reductionism as a hallmark of modern science, he claims that math can venture into “the most basic reductionist levels of explaining how natural phenomena work,” where language “fail[s].”

At its best, “The Great Rift” provides a robust account of how mathematics came of age as the principal means of explaining scientific truths. Mr. Hobart presents familiar thinkers like Aristotle and Copernicus alongside more obscure ones like Hugh of St. Victor and Robert Recorde, both of whom contributed to the development of mathematics. Before Galileo, Mr. Hobart argues, mathematics was guided by preconceived notions of the real world, established by philosophical and theological narratives. Mathematics was one means of representing that logos-centric reality but not the dominant one.

Math in the medieval world was subordinate to literacy and writing, but it was respected within this hierarchy. For example, the celebrated eighth-century monk Bede used “simple arithmetic” to calculate the dating for Easter based upon “existing astronomical data.” Gerbert of Aurillac (the future Pope Sylvester II) obsessed over what we consider elementary mathematical truths, striving to incorporate them into his teaching curriculum. In the 14th century, a group of scholars known as the Oxford Calculators and Nicole Oresme, the bishop of Lisieux, developed the so-called mean speed theorem (a forerunner of Galileo’s law of falling bodies). Nevertheless, these mathematical moments remained contextualized in an intellectual world circumscribed by the “metaphysics” of logos.

Such examples, in Mr. Hobart’s telling, set the stage for the “moment of breach” and the “momentous consequences” of Galileo’s achievements. Mr. Hobart rightly directs our attention to Galileo’s research into motion, matter and time rather than to his famous conflict with the church over its geocentric teachings. Galileo’s discoveries, Mr. Hobart says, caused a “tectonic shift.” The “thing-mathematics” of the Middle Ages, where numbers refer to real things, was replaced by “relation-mathematics,” where numbers are abstract and can refer to an almost limitless number of possible relations and concepts. Taking center stage in Mr. Hobart’s narrative is Galileo’s insistence that abstract mathematics is sufficient to describe natural processes.Unfortunately, Mr. Hobart’s story effectively ends where the rift begins. He wraps up the last 350 years in an epilogue that summarizes the modern world as one in which “religion shrinks from science.” This laconic conclusion is frustrating. Having set science upon its mathematical course, Mr. Hobart assumes that his tale will continue unimpeded, come what may. He mentions the 19th-century efforts to bring science and religion back together but flatly states that after Charles Darwin these hopes vanished. It overlooks the work of 20th-century thinkers like Michael Polanyi and Karl Popper, who have claimed, in different ways, that the whole of a scientific system is more complex than the relations between its constituent parts. The use of modal logic and probability theory by philosophers of religion like Richard Swinburne and Alvin Plantinga goes unnoticed, even though Mr. Plantinga’s recent book, “Where the Conflict Really Lies,” provides a useful alternative to the state that Mr. Hobart leaves us in—trapped in a broken home with only one parent.Perhaps most fundamentally, Mr. Hobart glosses over the complex relations between literacy and numeracy within science. Although he nods to language’s continued role as important in “making sense . . . of the results,” he doesn’t communicate how essential this role actually is. Language provides the only means of answering the question why: why we ask the questions we do; why we cannot answer certain questions; why the questions and answers are important in the first place. Without this information, science is useless. But science is more than mathematics, and religion is more than Mr. Hobart’s characterization of it: a “mystery” wrapped in “narratives of religious beliefs.” Certainly, they speak different languages, but what unites them is the human subject, who is quite capable of operating on both sides of the rift.https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-great-rift-review-from-comity-to-culture-war-1531347117

ゼロ除算の発見は日本です:

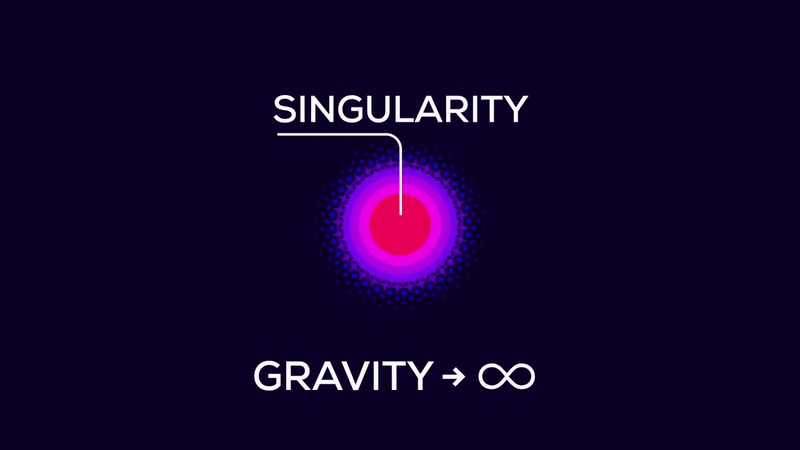

∞???

∞は定まった数ではない・

人工知能はゼロ除算ができるでしょうか:

とても興味深く読みました:

ゼロ除算の発見と重要性を指摘した:日本、再生核研究所

ゼロ除算関係論文・本

https://ameblo.jp/syoshinoris/entry-12370797278.html 再生核研究所声明 431(2018.7.14): y軸の勾配はゼロである - おかしな数学、おかしな数学界、おかしな雑誌界、おかしなマスコミ界?

2018年7月12日8時25分 ひとりでに湧いてきた。 おかしな私に おかしな構想が湧いてきた。ガリレオは つぶやいたという それでも地球は動いていると。 そのように、これは真実と素直な心情と思えるので 一気に纏めて置きたい。

まず、次の記録、事実を回想する: 今日、2018.6.3.15時ころ、あるテーブルで 6人で 食事をとっていた。隣の方が、大工さんだというので、真直ぐに立った柱の傾きは いくらでしょうかと少し説明して 問いました。 皆さん状況は 良く理解されていましたが、65歳くらいの姉妹 御婦人、石原芳子さん、清水きみ子さんが、ゼロじゃない? と結構当たり前のように おっしゃったのには 驚き、感銘を受けました。ゼロ除算から導かれた y軸の勾配がゼロは 相当に 感覚的にも当たり前であることが 分かります。発見当時、妻と息子に聞いた時も そうでした。真直ぐに立った 電柱の勾配は ゼロであると 言いました。これは 当たり前ではないでしょうか。所が 現代数学は 曖昧になっていて、分からない、不定のような 扱いになっています。おかしいですね。世界史の恥にならないでしょうか?

発見当時20年以上の友人ベルリン大学教授に ジョーク交じりに問うたところ、y軸の勾配は 右から近づけばプラス無限大、左から近づけばマイナス無限大で y軸自身の勾配は 考えられないとなっているという(記録No.-1:2015.9.17.05:45、No.-2:2015.9.18.19:15.)。

原点から出る直線の勾配で 考えられない例外の直線が存在して、それがy軸の方向であるということです。このような例外が存在するのは 理論として不完全であると言えます。それが常識外れとも言える結果、ゼロの勾配 を有するということです。この発見は 算術の確立者Brahmagupta (598 -668 ?) 以来の発見で、 ゼロ除算の意味の発見と結果1/0=0/0=0から導かれた具体的な結果です。

それは、微分係数の概念の新な発見やユークリッド以来の我々の空間の認識を変える数学ばかりではなく 世界観の変更を求める大きな事件に繋がります。そこで、日本数学会でも関数論分科会、数学基礎論・歴史分科会,代数学分科会、関数方程式分科会、幾何学分科会などでも それぞれの分科会の精神を尊重する形でゼロ除算の意義を述べてきました。招待された国際会議やいろいろな雑誌にも論文を出版している。イギリスの出版社と著書出版の契約も済ませている。

2014年 発見当時から、馬鹿げているように これは世界史上の事件であると公言して、世の理解を求めてきていて、詳しい経過なども できるだけ記録を残すようにしている。

これらは数学教育・研究の基礎に関わるものとして、日本数学会にも直接広く働きかけている。何故なら、我々の数学の基礎には大きな欠陥があり、我々の学術書は欠陥に満ちているからである。どんどん理解者が 増大する状況は有るものの依然として上記真実に対して、数学界、学術雑誌関係者、マスコミ関係の対応の在り様は誠におかしいのではないでしょうか。 我々の数学や空間の認識は ユークリッド以来、欠陥を有し、我々の数学は 基本的な欠陥を有していると800件を超える沢山の具体例を挙げて 示している。真実を求め、教育に真摯な人は その真相を求め、真実の追求を始めるべきではないでしょうか。 雑誌やマスコミ関係者も 余りにも基礎的な問題提起に 真剣に取り組まれるべきでは ないでしょうか。最も具体的な結果 y軸の勾配は どうなっているか、究めようではありませんか。それがゼロ除算の神秘的な歴史やユークリッド以来の我々の空間の認識を変える事件に繋がっていると述べているのです。 それらがどうでも良いは おかしいのではないでしょうか。人類未だ未明の野蛮な存在に見える。ゼロ除算の世界が見えないようでは、未だ夜明け前と言われても仕方がない。

以 上

2018年7月12日8時25分 ひとりでに湧いてきた。 おかしな私に おかしな構想が湧いてきた。ガリレオは つぶやいたという それでも地球は動いていると。 そのように、これは真実と素直な心情と思えるので 一気に纏めて置きたい。

まず、次の記録、事実を回想する: 今日、2018.6.3.15時ころ、あるテーブルで 6人で 食事をとっていた。隣の方が、大工さんだというので、真直ぐに立った柱の傾きは いくらでしょうかと少し説明して 問いました。 皆さん状況は 良く理解されていましたが、65歳くらいの姉妹 御婦人、石原芳子さん、清水きみ子さんが、ゼロじゃない? と結構当たり前のように おっしゃったのには 驚き、感銘を受けました。ゼロ除算から導かれた y軸の勾配がゼロは 相当に 感覚的にも当たり前であることが 分かります。発見当時、妻と息子に聞いた時も そうでした。真直ぐに立った 電柱の勾配は ゼロであると 言いました。これは 当たり前ではないでしょうか。所が 現代数学は 曖昧になっていて、分からない、不定のような 扱いになっています。おかしいですね。世界史の恥にならないでしょうか?

発見当時20年以上の友人ベルリン大学教授に ジョーク交じりに問うたところ、y軸の勾配は 右から近づけばプラス無限大、左から近づけばマイナス無限大で y軸自身の勾配は 考えられないとなっているという(記録No.-1:2015.9.17.05:45、No.-2:2015.9.18.19:15.)。

原点から出る直線の勾配で 考えられない例外の直線が存在して、それがy軸の方向であるということです。このような例外が存在するのは 理論として不完全であると言えます。それが常識外れとも言える結果、ゼロの勾配 を有するということです。この発見は 算術の確立者Brahmagupta (598 -668 ?) 以来の発見で、 ゼロ除算の意味の発見と結果1/0=0/0=0から導かれた具体的な結果です。

それは、微分係数の概念の新な発見やユークリッド以来の我々の空間の認識を変える数学ばかりではなく 世界観の変更を求める大きな事件に繋がります。そこで、日本数学会でも関数論分科会、数学基礎論・歴史分科会,代数学分科会、関数方程式分科会、幾何学分科会などでも それぞれの分科会の精神を尊重する形でゼロ除算の意義を述べてきました。招待された国際会議やいろいろな雑誌にも論文を出版している。イギリスの出版社と著書出版の契約も済ませている。

2014年 発見当時から、馬鹿げているように これは世界史上の事件であると公言して、世の理解を求めてきていて、詳しい経過なども できるだけ記録を残すようにしている。

これらは数学教育・研究の基礎に関わるものとして、日本数学会にも直接広く働きかけている。何故なら、我々の数学の基礎には大きな欠陥があり、我々の学術書は欠陥に満ちているからである。どんどん理解者が 増大する状況は有るものの依然として上記真実に対して、数学界、学術雑誌関係者、マスコミ関係の対応の在り様は誠におかしいのではないでしょうか。 我々の数学や空間の認識は ユークリッド以来、欠陥を有し、我々の数学は 基本的な欠陥を有していると800件を超える沢山の具体例を挙げて 示している。真実を求め、教育に真摯な人は その真相を求め、真実の追求を始めるべきではないでしょうか。 雑誌やマスコミ関係者も 余りにも基礎的な問題提起に 真剣に取り組まれるべきでは ないでしょうか。最も具体的な結果 y軸の勾配は どうなっているか、究めようではありませんか。それがゼロ除算の神秘的な歴史やユークリッド以来の我々の空間の認識を変える事件に繋がっていると述べているのです。 それらがどうでも良いは おかしいのではないでしょうか。人類未だ未明の野蛮な存在に見える。ゼロ除算の世界が見えないようでは、未だ夜明け前と言われても仕方がない。

以 上

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿