Albert Einstein’s Judaism

Albert Einstein, the greatest physicist since Isaac Newton, was a Jew. That is a simple and obvious statement, but what does it mean?

Einstein’s relationship with his Judaism evolved as did his science — slowly over time, in complex fashion. The General Theory of Relativity was not born overnight, and neither was Einstein’s eventual strong affiliation with Judaism and Israel.

Walter Isaacson writes in his magisterial biography that both of Einstein’s parents were Jewish and traced their ancestry back more than 200 years in Germany. They had assimilated into German culture and were completely secular. Albert was born in 1879, and they were going to name him Abraham, but decided that it sounded too Jewish.

Albert attended a Catholic elementary school. Although the teachers did not discriminate against him, his fellow students did. They insulted him and beat him. He learned at an early age that being Jewish in Germany was to be an outsider.

In high school, a Jewish teacher was hired to provide Jewish students with instruction in Judaism and — initially — Albert took to it enthusiastically, keeping kosher and Shabbat. That did not last long.

Einstein encountered antisemitism when he launched his career as well. After graduating from university, and even after earning a doctorate and formulating the Theory of Relativity, he received no job offers and ended up working in a patent office in the Post and Telegraph building.

He was offered a professorship in 1909 at the University of Zurich, but there were strong reservations because of his Judaism. A letter from the faculty mentioned that Einstein did not exhibit any of the usual Jewish characteristics — “all kinds of unpleasant peculiarities of character, such as intrusiveness, impudence, and a shopkeeper’s mentality in the perception of their academic position.”

Because of his increasing fame as a genius of science, Einstein met with important people like Chaim Weizmann, a fellow scientist and ardent Zionist. Together, they went to America to seek support for the establishment of a Jewish university in Palestine, which would become the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. On his way back in 1922, he made his only trip to Palestine, where he stayed for 12 days and was received like a head of state.

Seeing Jews working on building a new state, he was deeply impressed. He wrote: “Today, I have been made happy by the sight of the Jewish people learning to recognize themselves and to make themselves recognized as a force in the world.”

If Einstein could not accept organized religion or believe in a personal God who intervened in history, he did consider himself religious in one sense: “Try and penetrate with our limited means the secrets of nature and you will find that, behind all the discernible laws and connections, there remains something subtle, intangible, and inexplicable. Veneration for this force beyond anything that we can comprehend is my religion.”

Clearly, study of the universe inspired in him a sense of awe and wonder.

As he turned 50, Einstein’s appreciation for his Jewish identity intensified. He did not believe in free will or immortality, but he valued Judaism’s emphasis on social justice. “Striving for social justice,” he wrote, “is the most valuable thing to do in life.”

He declared that he was not an atheist: “We are in the position of a little child entering a huge library filled with books in many languages. The child knows that someone must have written those books. It does not know how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. The child dimly suspects a mysterious order in the arrangement of the books but does not know what it is. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of even the most intelligent human being toward God.”

To a schoolgirl’s letter inquiring about religion, he wrote, “Everyone who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit is manifest in the laws of the Universe — a spirit vastly superior to that of man, and one in the face of which we with our modest powers must feel humble.”

Finally, he described radical atheists as those who “cannot hear the music of the spheres.”

In 1932, Einstein became a refugee. He left Berlin for America; his third visit. The Nazis raided his cottage at Caputh and he never returned to Germany. The Nazis even turned on his science, declaring it relativist — confusing relativity with relativism — and non-Aryan. They appointed the arch antisemite Philipp Lenard as the new chief of Aryan science.

Einstein was moved to write an article that year — “Why Do They Hate the Jews?” — in which he declared that Jews have always shared “the democratic ideal of social justice coupled with the ideal of mutual aid and tolerance among all men.” In that spirit, he threw his support behind the struggle for civil rights in America.

He spent his last years promoting the concept of world government to prevent war and, as a result, was under scrutiny by the FBI, which had a file of 1,427 pages on him. He declared that he was not a German but “a Jew by nationality” and compared himself to Cervantes’s Don Quixote, because he resembled the great character of the novel in his tilting at windmills.

Einstein considered his relationship with the Jewish people “my strongest human tie once I achieved complete clarity about our precarious position among the nations of the world.” The Israeli diplomat Abba Eban met with Einstein in 1955. Einstein told him that he saw the establishment of the State of Israel as one of the few political acts in his lifetime that had a moral quality.

Albert Einstein began his life as a secular, assimilated German Jew — a brilliant mind focused on the universe beyond our tiny planet — and ended up a committed Zionist, a man clearly dedicated to the advancement of world peace and the welfare of his own people, a man very much of this Earth. He reached an understanding of the stars, yet his other great discovery was his own people and its culture.

Dr. Paul Socken is Distinguished Professor Emeritus and founder of the Jewish Studies program at the University of Waterloo.

The opinions presented by Algemeiner bloggers are solely theirs and do not represent those of The Algemeiner, its publishers or editors. If you would like to share your views with a blog post on The Algemeiner, please be in touch through our Contact page.https://www.algemeiner.com/2018/07/19/albert-einsteins-judaism/

ゼロ除算の発見は日本です:

∞???

∞は定まった数ではない・・・

人工知能はゼロ除算ができるでしょうか:

とても興味深く読みました:

ゼロ除算の発見と重要性を指摘した:日本、再生核研究所

ゼロ除算関係論文・本

再生核研究所声明 277(2016.01.26):アインシュタインの数学不信 ― 数学の欠陥

(山田正人さん:散歩しながら、情念が湧きました:2016.1.17.10時ころ 散歩中)

西暦628年インドでゼロが記録され、四則演算が考えられて、1300年余、ようやく四則演算の法則が確立された。ゼロで割れば、何時でもゼロになるという美しい関係が発見された。ゼロでは割れない、ゼロで割ることを考えてはいけないは 1000年を超える世界史の常識であり、天才オイラーは それは、1/0は無限であるとの論文を書き、無限遠点は 複素解析学における100年を超える定説、確立した学問である。割り算を掛け算の逆と考えれば、ゼロ除算が不可能であることは 数学的に簡単に証明されてしまう。

しかしながら、ニュートンの万有引力の法則,アインシュタインの特殊相対性理論にゼロ除算は公式に現れていて、このような数学の常識が、物理的に解釈できないジレンマを深く内蔵してきた。そればかりではなく、アリストテレスの世界観、ゼロの概念、無とか、真空の概念での不可思議さゆえに2000年を超えて、議論され、そのため、ゼロ除算は 神秘的な話題 を提供させてきた。実際、ゼロ除算の歴史は ニュートンやアインシュタインを悩ましてきたと考えられる。

ニュートンの万有引力の法則においては 2つの質点が重なった場合の扱いであるが、アインシュタインの特殊相対性理論においては ローレンツ因子 にゼロになる項があるからである。

特にこの点では、深刻な矛盾、問題を抱えていた。

特殊相対性理論では、光速の速さで運動しているものの質量はゼロであるが、光速に近い速さで運動するものの質量(エネルギー)が無限に発散しているのに、ニュートリノ素粒子などが、光速に極めて近い速度で運動しているにも拘わらず 小さな質量、エネルギーを有しているという矛盾である。

そこで、この矛盾、ゼロ除算の解釈による矛盾に アインシュタインが深刻に悩んだものと思考される。実際 アインシュタインは 数学不信を公然と 述べている:

What does Einstein mean when he says, "I don't believe in math"?

アインシュタインの数学不信の主因は アインシュタインが 難解で抽象的な数学の理論に嫌気が差したものの ゼロ除算の間違った数学のためである と考えられる。(次のような記事が見られるが、アインシュタインが 逆に間違いをおかしたのかは 大いに気になる:Sunday, 20 May 2012

簡単なゼロ除算について 1300年を超える過ちは、数学界の歴史的な汚点であり、物理学や世界の文化の発展を遅らせ、それで、人類は 猿以下の争いを未だに続けていると考えられる。

数学界は この汚名を速やかに晴らして、数学の欠陥部分を修正、補充すべきである。 そして、今こそ、アインシュタインの数学不信を晴らすべきときである。数学とは本来、完全に美しく、永遠不滅の、絶対的な存在である。― 実際、数学の論理の本質は 人類が存在して以来 どんな変化も認められない。数学は宇宙の運動のように人間を離れた存在である。

再生核研究所声明で述べてきたように、ゼロ除算は、数学、物理学ばかりではなく、広く人生観、世界観、空間論を大きく変え、人類の夜明けを切り拓く指導原理になるものと思考される。

以 上

Impact of ‘Division by Zero’ in Einstein’s Static Universe and Newton’s Equations in Classical Mechanics. Ajay Sharma physicsajay@yahoo.com Community Science Centre. Post Box 107 Directorate of Education Shimla 171001 India

Key Words Aristotle, Universe, Einstein, Newton http://gsjournal.net/Science-Journals/Research%20Papers-Relativity%20Theory/Download/2084

再生核研究所声明 278(2016.01.27): 面白いゼロ除算の混乱と話題

Googleサイトなどを参照すると ゼロ除算の話題は 膨大であり、世にも珍しい現象と言える(division by zero: 約298 000 000結果(0.51秒)

検索結果

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Division_by_zero

数学では、ゼロ除算は、除数(分母)がゼロである部門です。このような部門が正式に配当である/ 0をエスプレッソすることができます(2016.1.19.13:45)).

問題の由来は、西暦628年インドでゼロが記録され、四則演算が考えられて、1300年余、ゼロでは割れない、ゼロで割ることを考えてはいけないは 1000年を超える世界史の常識であり、天才オイラーは それは、1/0は無限であるとの論文を書き、無限遠点は 複素解析学における100年を超える定説、確立した学問である。割り算を掛け算の逆と考えれば、ゼロ除算が不可能であることは 数学的に簡単に証明されてしまう。しかしながら、アリストテレスの世界観、ゼロの概念、無とか、真空の概念での不可思議さゆえに2000年を超えて、議論され、そのため、ゼロ除算は 神秘的な話題 を提供させてきた。

確定した数学に対していろいろな存念が湧き、話題が絶えないことは 誠に奇妙なことと考えられる。ゼロ除算には 何か問題があるのだろうか。

先ず、多くの人の素朴な疑問は、加減乗除において、ただひとつの例外、ゼロで割ってはいけないが、奇妙に見えることではないだろうか。例外に気を惹くは 何でもそうであると言える。しかしながら、より広範に湧く疑問は、物理の基本法則である、ニュートンの万有引力の法則,アインシュタインの特殊相対性理論に ゼロ除算が公式に現れていて、このような数学の常識が、物理的に解釈できないジレンマを深く内蔵してきた。実際、ゼロ除算の歴史は ニュートンやアインシュタインを悩ましてきたと考えられる。

ニュートンの万有引力の法則においては 2つの質点が重なった場合の扱いであるが、アインシュタインの特殊相対性理論においては ローレンツ因子 にゼロになる項があるからである。

特にこの点では、深刻な矛盾、問題を抱えていた。

特殊相対性理論では、光速の速さで運動しているものの質量はゼロであるが、光速に近い速さで運動するものの質量(エネルギー)が無限に発散しているのに、ニュートリノ素粒子などが、光速に極めて近い速度で運動しているにも拘わらず 小さな質量、エネルギーを有しているという矛盾である。それゆえにブラックホール等の議論とともに話題を賑わしてきている。最近でも特殊相対性理論とゼロ除算、計算機科学や論理の観点でゼロ除算が学術的に議論されている。次のような極めて重要な言葉が残されている:

George Gamow (1904-1968) Russian-born American nuclear physicist and cosmologist remarked that "it is well known to students of high school algebra" that division by zero is not valid; and Einstein admitted it as the biggest blunder of his life [1]:

1. Gamow, G., My World Line (Viking, New York). p 44, 1970

スマートフォン等で、具体的な数字をゼロで割れば、答えがまちまち、いろいろなジョーク入りの答えが出てくるのも興味深い。しかし、計算機がゼロ除算にあって、実際的な障害が起きた:

ヨークタウン (ミサイル巡洋艦)ヨークタウン(USS Yorktown, DDG-48/CG-48)は、アメリカ海軍のミサイル巡洋艦。タイコンデロガ級ミサイル巡洋艦の2番艦。艦名はアメリカ独立戦争のヨークタウンの戦いにちなみ、その名を持つ艦としては5隻目。

艦歴[編集]

1997年9月21日バージニア州ケープ・チャールズ沿岸を航行中に、乗組員がデータベースフィールドに0を入力したために艦に搭載されていたRemote Data Base Managerでゼロ除算エラーが発生し、ネットワーク上の全てのマシンのダウンを引き起こし2時間30分にわたって航行不能に陥った。 これは搭載されていたWindows NT 4.0そのものではなくアプリケーションによって引き起こされたものだったが、オペレーティングシステムの選択への批判が続いた。[1]

2004年12月3日に退役した。

出典・脚注[編集]

1. ^ Slabodkin, Gregory (1998年7月13日). “Software glitches leave Navy Smart Ship dead in the water”. Government Computer News. 2009年6月18日閲覧。

これはゼロ除算が不可能であるから、計算機がゼロ除算にあうと、ゼロ除算の誤差動で重大な事故につながりかねないことを実証している。それでゼロ除算回避の数学を考えている研究者もいる。論理や計算機構造を追求して、代数構造を検討したり、新しい数を導入して、新しい数体系を提案している。

確立している数学について話題が尽きないのは、思えば、ゼロ除算について、何か本質的な問題があるのだろうかと考えられる。 火のないところに煙は立たないという諺がある。 ゼロ除算は不可能であると 考えるか、無限遠点の概念、無限か と考えるのが 数百年間を超える数学の定説であると言える。

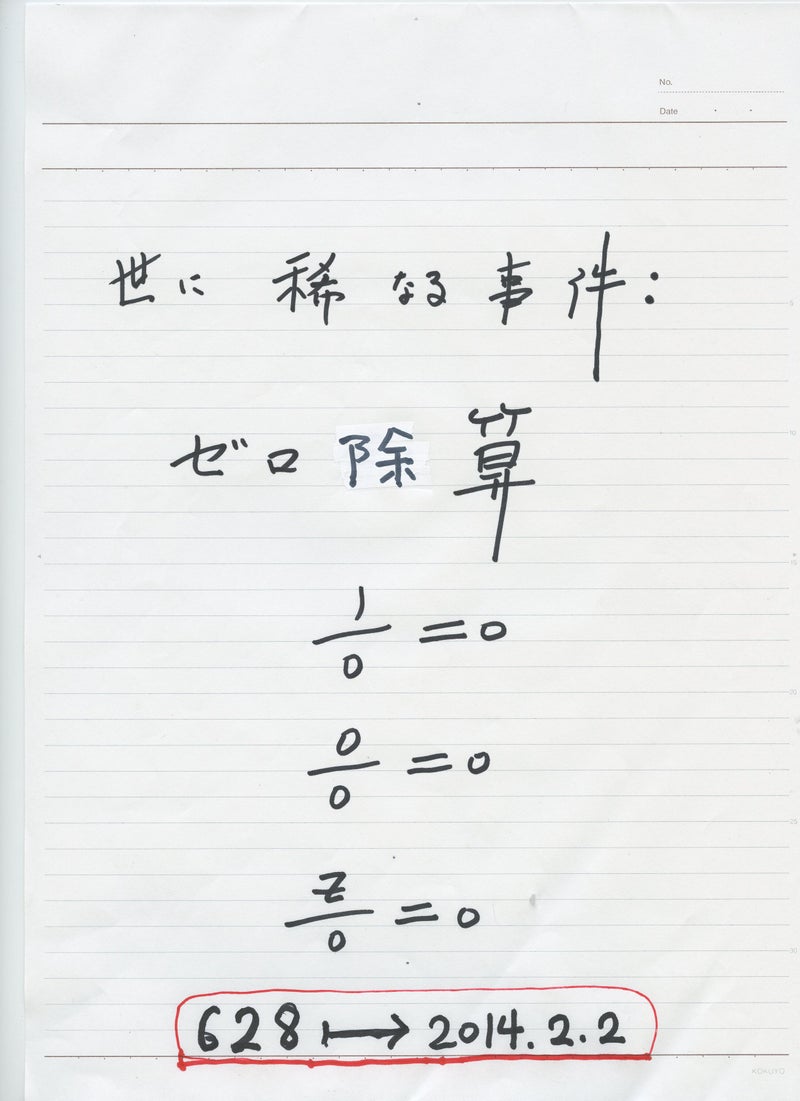

ところがその定説が、 思いがけない形で、完全に覆り、ゼロ除算は何時でも可能で、ゼロで割れば何時でもゼロになるという美しい結果が 2014.2.2 発見された。 結果は3篇の論文に既に出版され、日本数会でも発表され、大きな2つの国際会議でも報告されている。 ゼロ除算の詳しい解説も次で行っている:

○ 堪らなく楽しい数学-ゼロで割ることを考える(18)

○ 堪らなく楽しい数学-ゼロで割ることを考える(18)

数学基礎学力研究会のホームページ

URLは

また、再生核研究所声明の中でもいろいろ解説している。

以 上

再生核研究所声明 279(2016.01.28) ゼロ除算の意義

ここでは、ゼロ除算発見2周年目が近づいた現時点における ゼロ除算100/0=0, 0/0=0の意義を箇条書きで纏めて置こう。

1)。西暦628年インドでゼロが記録されて以来 ゼロで割るという問題 に 簡明で、決定的な解決をもたらした。数学として完全な扱いができたばかりか、結果が世の普遍的な現象を表現していることが実証された。それらは3篇の論文に公刊され、第4論文も出版が決まり、さらに4篇の論文原稿があり、討論されている。2つの大きな国際会議で報告され、日本数学会でも2件発表され、ゼロ除算の解説(2015.1.14;14ページ)を1000部印刷配布、広く議論している。また, インターネット上でも公開で解説している:

○ 堪らなく楽しい数学-ゼロで割ることを考える(18)

○ 堪らなく楽しい数学-ゼロで割ることを考える(18)

数学基礎学力研究会のホームページ

2) ゼロ除算の導入で、四則演算 加減乗除において ゼロでは 割れない の例外から、例外なく四則演算が可能である という 美しい四則演算の構造が確立された。

3)2千年以上前に ユークリッドによって確立した、平面の概念に対して、おおよそ200年前に非ユークリッド幾何学が出現し、特に楕円型非ユークリッド幾何学ではユークリッド平面に対して、無限遠点の概念がうまれ、特に立体射影で、原点上に球をおけば、 原点ゼロが 南極に、無限遠点が 北極に対応する点として 複素解析学では 100年以上も定説とされてきた。それが、無限遠点は 数では、無限ではなくて、実はゼロが対応するという驚嘆すべき世界観をもたらした。

4)ゼロ除算は ニュートンの万有引力の法則における、2点間の距離がゼロの場合における新しい解釈、独楽(コマ)の中心における角速度の不連続性の解釈、衝突などの不連続性を説明する数学になっている。ゼロ除算は アインシュタインの理論でも重要な問題になっていて、特殊相対性理論やブラックホールなどの扱いに重要な新しい視点を与える。数多く存在する物理法則を記述する方程式にゼロ除算が現れているが、それらに新解釈を与える道が拓かれた。次のような極めて重要な言葉に表されている:

George Gamow (1904-1968) Russian-born American nuclear physicist and cosmologist remarked that "it is well known to students of high school algebra" that division by zero is not valid; and Einstein admitted it as the biggest blunder of his life [1]:

1. Gamow, G., My World Line (Viking, New York). p 44, 1970

5)複素解析学では、1次分数変換の美しい性質が、ゼロ除算の導入によって、任意の1次分数変換は 全複素平面を全複素平面に1対1 onto に写すという美しい性質に変わるが、極である1点において不連続性が現れ、ゼロ除算は、無限を 数から排除する数学になっている。

6)ゼロ除算は、不可能であるという立場であったから、ゼロで割る事を 本質的に考えてこなかったので、ゼロ除算で、分母がゼロである場合も考えるという、未知の新世界、新数学、研究課題が出現した。

7)複素解析学への影響は 未知の分野で、専門家の分野になるが、解析関数の孤立特異点での性質について新しいことが導かれる。典型的な定理は、どんな解析関数の孤立特異点でも、解析関数は 孤立特異点で、有限な確定値をとる である。佐藤の超関数の理論などへの応用がある。

8)特異積分におけるアダマールの有限部分や、コーシーの主値積分は、弾性体やクラック、破壊理論など広い世界で、自然現象を記述するのに用いられている。面白いのは 積分が、もともと有限部分と発散部分に分けられ、極限は 無限たす、有限量の形になっていて、積分は 実は、普通の積分ではなく、そこに現れる有限量を便宜的に表わしている。ところが、その有限量が実は、ゼロ除算にいう、解析関数の孤立特異点での 確定値に成っていること。いわゆる、主値に対する解釈を与えている。これはゼロ除算の結果が、広く、自然現象を記述していることを示している。

9)中学生や高校生にも十分理解できる基本的な結果をもたらした:

基本的な関数y = 1/x のグラフは、原点で ゼロである;すなわち、 1/0=0 である。

基本的な関数y = 1/x のグラフは、原点で ゼロである;すなわち、 1/0=0 である。

10)既に述べてきたように 道脇方式は ゼロ除算の結果100/0=0, 0/0=0および分数の定義、割り算の定義に、小学生でも理解できる新しい概念を与えている。多くの教科書、学術書を変更させる大きな影響を与える。

11)ゼロ除算が可能であるか否かの議論について:

現在 インターネット上の情報でも 世間でも、ゼロ除算は 不可能であるとの情報が多い。それは、割り算は 掛け算の逆であるという、前提に議論しているからである。それは、そのような立場では、勿論 正しいことである。出来ないという議論では、できないから、更には考えられず、その議論は、不可能のゆえに 終わりになってしまう ― もはや 展開の道は閉ざされている。しかるに、ゼロ除算が 可能であるとの考え方は、それでは、どのような理論が 展開できるのかの未知の分野が望めて、大いに期待できる世界が拓かれる。

12)ゼロ除算は、数学ばかりではなく、人生観、世界観や文化に大きな影響を与える。

次を参照:

再生核研究所声明166(2014.6.20)ゼロで割る(ゼロ除算)から学ぶ 世界観

再生核研究所声明188(2014.12.16)ゼロで割る(ゼロ除算)から観えてきた世界

再生核研究所声明262 (2015.12.09) 宇宙回帰説 ― ゼロ除算の拓いた世界観 。

ゼロ除算における新現象、驚きとは Aristotélēs の世界観、universe は連続である を否定して、強力な不連続性を universe の現象として受け入れることである。

13) ゼロ除算は ユークリッド幾何学にも基本的に現れ、いわば、素朴な無限遠点に関係するような平行線、円と直線の関係などで本質的に新しい現象が見つかり、現実の現象の説明に合致する局面が拓かれた。

14) 最近、3つのグループの研究に遭遇した:

論理、計算機科学 代数的な体の構造の問題(J. A. Bergstra, Y. Hirshfeld and J. V. Tucker)、

特殊相対性の理論とゼロ除算の関係(J. P. Barukcic and I. Barukcic)、

計算器がゼロ除算に会うと実害が起きることから、ゼロ除算回避の視点から、ゼロ除算の検討(T. S. Reis and James A.D.W. Anderson)。

これらの理論は、いずれも不完全、人為的で我々が確定せしめたゼロ除算が、確定的な数学であると考えられる。世では、未だゼロ除算について不可思議な議論が続いているが、数学的には既に確定していると考えられる。

そこで、これらの認知を求め、ゼロ除算の研究の促進を求めたい:

再生核研究所声明 272(2016.01.05): ゼロ除算の研究の推進を、

再生核研究所声明259(2015.12.04): 数学の生態、旬の数学 ―ゼロ除算の勧め。

以 上

再生核研究所声明280(2016.01.29) ゼロ除算の公認、認知を求める

ゼロで割ること、すなわち、ゼロ除算は、西暦628年インドでゼロが記録されて以来の懸案の問題で、神秘的な話題を提供してきた。最新の状況については声明279を参照。ゼロ除算は 数学として完全な扱いができたばかりか、結果が世の普遍的な現象を表現していることが実証された。それらは3篇の論文に公刊され、第4論文も出版が決まり、さらに4篇の論文原稿があり、討論されている。2つの招待された国際会議で報告され、日本数学会でも2件発表された。また、ゼロ除算の解説(2015.1.14;14ページ)を1000部印刷配布、広く議論している。さらに, インターネット上でも公開で解説している:

○ 堪らなく楽しい数学-ゼロで割ることを考える(18)

○ 堪らなく楽しい数学-ゼロで割ることを考える(18)

数学基礎学力研究会のホームページ

最近、3つの研究グループに遭遇した:

論理、計算機科学、代数的な体の構造の問題(J. A. Bergstra, Y. Hirshfeld and J. V. Tucker)、

特殊相対性の理論とゼロ除算の関係(J. P. Barukcic and I. Barukcic)、

計算器がゼロ除算に会うと実害が起きることから、ゼロ除算回避の視点から、ゼロ除算の研究(T. S. Reis and James A.D.W. Anderson)。

これらの理論は、いずれも不完全、人為的で我々が確定せしめたゼロ除算が、確定的な数学であると考える。世では、未だゼロ除算について不可思議な議論が続いているが、数学的には既に確定していると考える。

ゼロ除算について、不可能であるとの認識、議論は、簡単なゼロ除算について 1300年を超える過ちであり、数学界の歴史的な汚点である。そのために数学を始め、物理学や世界の文化の発展を遅らせ、それで、人類は 猿以下の争いを未だ続けていると考えられる。

数学界は この汚名を速やかに晴らして、数学の欠陥部分を修正、補充すべきである。 そして、今こそ、アインシュタインの数学不信を晴らすべきときである。数学とは本来、完全に美しく、永遠不滅の、絶対的な存在である。― 実際、数学の論理の本質は 人類が存在して以来 どんな変化も認められない。数学は宇宙の運動のように人間を離れた存在である。

再生核研究所声明で述べてきたように、ゼロ除算は、数学、物理学ばかりではなく、広く人生観、世界観、空間論を大きく変え、人類の夜明けを切り拓く指導原理になるものと考える。

そこで、発見から、2年目を迎えるのを期に、世の影響力のある方々に ゼロ除算の結果の公認、社会的に 広い認知が得られるように 協力を要請したい。

文献:

1) J. P. Barukcic and I. Barukcic, Anti Aristotle - The Division Of Zero By Zero,

ViXra.org (Friday, June 5, 2015)

© Ilija Barukčić, Jever, Germany. All rights reserved. Friday, June 5, 2015 20:44:59.

2) J. A. Bergstra, Y. Hirshfeld and J. V. Tucker,

Meadows and the equational specification of division (arXiv:0901.0823v1[math.RA] 7 Jan 2009).

3) M. Kuroda, H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh, and M. Yamane,

New meanings of the division by zero and interpretations on $100/0=0$ and on $0/0=0$, Int. J. Appl. Math. {\bf 27} (2014), no 2, pp. 191-198, DOI:10.12732/ijam.v27i2.9.

4) H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh, and M.Yamada,

Reality of the division by zero $z/0=0$. IJAPM (International J. of Applied Physics and Math. 6(2015), 1--8. http://www.ijapm.org/show-63-504-1.html

5) T. S. Reis and James A.D.W. Anderson,

Transdifferential and Transintegral Calculus, Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science 2014 Vol I WCECS 2014, 22-24 October, 2014, San Francisco, USA

6) T. S. Reis and James A.D.W. Anderson,

Transreal Calculus, IAENG International J. of Applied Math., 45: IJAM_45_1_06.

7) S. Saitoh, Generalized inversions of Hadamard and tensor products for matrices, Advances in Linear Algebra \& Matrix Theory. {\bf 4} (2014), no. 2, 87--95. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ALAMT/

7) S.-E. Takahasi, M. Tsukada and Y. Kobayashi, Classification of continuous fractional binary operations on the real and complex fields, Tokyo Journal of Mathematics, {\bf 38}(2015), no.2. 369-380.

8) Saitoh, S., A reproducing kernel theory with some general applications (31pages)ISAAC (2015) Plenary speakers 13名 による本が スプリンガーから出版される。

以 上

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿