ソクラテスから今日までの正義の進化

Everybody seems to like justice. Nearly every culture that has left us a written record of its thinking and way of life has elevated justice to the status of a cardinal virtue. The question of what justice is, however, has troubled leading minds for the last 3,000 years. Over time, the shift in what we consider justice to be is rather fascinating.

Here, we will compare ancient, medieval, and modern ideas of justice and see how far we have come.

Classical Justice

Socrates being put to death for corrupting the youth of Athens. Is this just? Or is the system that did this flawed? (Public domain)

Socrates being put to death for corrupting the youth of Athens. Is this just? Or is the system that did this flawed? (Public domain)

In Ancient Greece justice was viewed rather differently than it is today. As explained in Plato's Republic, viewing justice as harmony can lead to some very interesting ideas not only for how the individual should behave but also for how the state should be organized. Well, at least when Plato is doing the organizing.

For the individual, this means balancing the three parts of the soul: reason, spirit, and desire. The just individual does their duty in the right place and is fair in all dealings. Exactly how they will act is variable based on time and place, but a person with enough practical wisdom will know what to do.

For the city, this meant a rigid caste system ruled by philosopher kings with an iron fist and Orwellian control of daily life. This totalitarian system would assure every person was in their proper place and that the system would continue harmoniously. The interests of the individual had little claim to anything in this system as the interests of society were all that mattered.

Aristotle didn’t go so far as to argue for the totalitarian city-state of Republicbut did agree that different groups of people should be treated differently under the law. In Politics, he even argues that some persons are “natural slaves” and it is best for everyone if those people are enslaved rather than free.

Medieval Justice

The leading European mind of the Middle Ages was St. Thomas Aquinas. The patron saint of teachers, his thought covered nearly all areas of philosophic endeavor. His ideas of justice remain influential in the Catholic Church, and a more modern school of ethical and political theory based on his ideas, known as Thomism, continues to attract interest.

1) 法律、規則、慣習、約束に合っているか。

2) 逆の立場に立ってみてそれは受け入れられるか。

3) それはみんなに受け入れられるか。

4) それは安定的に実現可能か。

テーマ:社会

Aquinas argued for a system of justice based on proportional reciprocity. That is, each just person gives what is due to others in the measure that they are due. This won't be equal for everybody and what you owe them is going to be based not only on civil law but also on moral law. We should view ourselves as part of a community, he suggests, and our actions should also consider how to benefit everyone.

He also offers a shrewd way to view the virtue of justice. While even today it is not uncommon to hear the argument that an atheist cannot be trusted to be just as they don’t believe in divine reward and punishment, Aquinas shows us this is rather silly.

He understood that there were many things which could be understood by reason alone and did not require Christian faith to know. As the golden rule is one such thing, a non-Christian could be trusted to comprehend justice and act on it. This helped to legitimize pre-Christian and Islamic thought in a theocratic Europe that was suspicious of their heathen influence.

St. Aquinas also argued that there was such a thing as a “just price” for goods and services. He argues that while it is just to make a bit of profit, a seller that raises their prices in response to a spike in demand is acting unjustly. His theory of distributive justice isn’t as fleshed out as modern conceptions, however.

Modern Justice

Perhaps the most striking difference between modern justice and that of previous eras is our conception of egalitarianism. Nearly all societies today at least give lip service to the idea that all people are considered equal before the law.

This egalitarianism has its roots in the enlightenment thought of many philosophers, not the least of whom was Immanuel Kant and his stance that we should treat all people as ends in themselves and not as tools for our desires. While this equality was limited to men at first, the scope of who qualifies for equal rights has continued to expand ever since—if slowly and in fits and starts.

Today we also have a surplus of theories of distributive justice, something which was lacking before Adam Smith and his book The Wealth of Nations. This development is comparatively recent in intellectual history and proposals of distributive justice before Smith are not nearly so fleshed out.

Today we also have a surplus of theories of distributive justice, something which was lacking before Adam Smith and his book The Wealth of Nations. This development is comparatively recent in intellectual history and proposals of distributive justice before Smith are not nearly so fleshed out.

While Smith based his system on the market, others looked to moral justifications for their theories. Marx, Mill, Rawls, and Nozick all offer us differing ideas of how goods should be distributed in a society based on the inherent rights and moral claims of the individual in ways that thinkers in ages past never considered. While their ideas are beyond the scope of this article, the links will take you to explanations.

What justice is, how we reach it, and what it means to both us and the state are questions which have plagued the world for the last few thousand years. As we have seen, the answers that societies have settled on have changed dramatically in that time. While ideas of what justice is continue to evolve, it can edify us to see what changes have already occurred.

Most of us today would view the concepts of ancient Greece and the Middle Ages as barbaric; how will our ideas be viewed in the far future? To reflect on the ideas long since put aside can give context to ours, and aid us going forward. http://bigthink.com/scotty-hendricks/the-ever-changing-definition-of-justice

とても興味深く読みました:

再生核研究所声明 139 (2013.10.22):

正義とは 戦争における; 短期的には 勝者が決めるが、世界史が評価の大勢を定める

(2013.10.10.16:35 休んでいるとき、構想を練る。これは声明に関心を擁く人からの 要望による。)

まず、用語を確認して置こう:

正義(せいぎ、希: δικαιοσύνη、羅: jūstitia、英: justice、仏: justice、独: Gerechtigkeit)とは、倫理、合理性、法律、自然法、宗教、公正ないし衡平にもとづく道徳的な正しさ[要出典]に関する概念である。 正義の実質的な内容を探究する学問分野は正義論と呼ばれる。広義すなわち日本語の日常的な意味においては、道理に適った正しいこと全般を意味する。以下では、専ら西洋における概念(すなわちjusticeないしそれに類似する言葉で示されるもの)を記述する。東洋のそれについては義のページを参照。

定義[編集]

正義とは、それ自体に鑑みれば、社会における物および人に関する固有の秩序である[要出典]。この概念は、哲学的、法的あるいは神学的な影響の下で、歴史上絶え間なく論じられてきた。正義に関する問題の多くは、西洋における正義概念に依拠している。例えば、「正義とは何であるか」「正義は個人および社会に何を要求しているか」「社会における財と資源の本来的な配分方法(平等主義、才能主義、身分主義)は何か」などである。これらの問いに対しては、政治および哲学に関する多様な観点から様々に答えうる。 正義の概念は、多くの正義論によって極めて重要な概念であるとされている。例えば、ジョン・ロールズは次のように述べている[1]。「正義とは、思想体系が真であることとしての、社会制度の根本的な徳である」。正義は、親切、慈悲、慈愛、寛大さあるいは共感などのその他の徳と区別され、そしてそれらよりもより基本的な徳であると考えることもできる。正義は、とりわけギリシャ哲学やキリスト教においては、運命、輪廻あるいは神の予見のように、自然の摂理や超越的存在によって規律された生ないし生き方と結び付けられることがしばしばであった。しかし、現代の正義論においては、このような宇宙論的・宗教的世界観を離れて、正義を社会制度の根源を為す価値である公正さと結び付けて人間社会の枠組みの問題であると捉える傾向が強い。(http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E6%AD%A3%E7%BE%A9より)

また、

義

|

「羊」 を含むのは、祥・善 に羊を含むのと同じく、ヒツジを神に捧げるギセイに常用した習慣に基づく。

もともと宜 と同じく神への供物が くっきりとかどばって美しく揃っていること。

<書経、文侯之命> の「父義和」の鄭注に、「義とは匹(そろう)なり」とあるのは、なお原義に近い。

<礼記、中庸> に「義とは宜なり」とある。また<礼記、祭義> に「義とはこれに宜(よろ)しきなり」ともある。

|

また、

ここで再び唐漢氏に登場願う。彼曰く、

甲骨文字「義」

|

金文「義」

|

「義」という字は、羊と我という文字から成り立っている。ここで「羊」はこの種の頭上にある大きく湾曲した角を指す。その意味は羊の統率指導権や交配優先権を表すものだと解釈されている。そして「我」というのは古代の長い柄の一種の兵器のことであるが、形が美しく作られ実際の戦闘には不向きで、軍隊の標識用に作られたものだとしている。したがって「義」という字は、本来は「羊」の頭を指し自分あるいはグループの権力、戦闘に向かう集団の権力の誇示に並べたものであろうということである。

このことから「義」は情理・正義に合致した名目の立つ出兵を示し、公正適切な言行を指すようになったということである。

このことから考えると先ごろのアメリカ・イギリスなどのイラク攻撃には一体いかなる「義」が存在したのだろう。一旦この「義」が地に捨てられてしまうと、後は強肉弱食のカオスの世界しか残らない。

このことを「天地人」の作者は最も言いたかったのではないだろうか。

また、

上記のように “正義” は 実に曖昧な言葉であることが分る。 義の語源から、戦闘を大義名分にするときに掲げる言語で、重い意味を有する言語ではないだろうか。そこで、正義の意味をきちんとさせたい。 きちんとした解釈を与えたい。

まず、世の道徳や、法や慣習が確立している範囲ならば、正義は 次の 公正の原則 で定められるのではないだろうか:

再生核研究所声明 1 (2007/1/27): 美しい社会はどうしたら、できるか、 美しい社会とは:

平成12年9月21日早朝、公正とは何かについて次のような考えがひらめいて目を覚ました。(公正の原則)

平成12年9月21日早朝、公正とは何かについて次のような考えがひらめいて目を覚ました。(公正の原則)

1) 法律、規則、慣習、約束に合っているか。

2) 逆の立場に立ってみてそれは受け入れられるか。

3) それはみんなに受け入れられるか。

4) それは安定的に実現可能か。

ところが、合戦や戦争では いわゆる約束ごと、ルールを越えて 行われるので、世の一切の法やルール、慣習を越えている。それで、その戦いを正当化する言語、正義は、極めて難しい言語であると言える。ルールは何も無く、ただ戦争の勝利者が正義を定められる と考えるべきである。これは既に 定着している 勝てば官軍 の諺に表現される。合戦には 不意打ち、だまし討ち、陰謀などは常識であり、侵略どころか、虐殺、皆殺しなども世界史には存在する。第二次世界大戦でも 戦闘力のない 敗戦真近かの国に 非戦闘員、民間人の大量虐殺を始めから意図した原爆投下などが 存在するが、戦争だから仕方がないと 世界では受け止められている。 非戦闘員は 巻添えにはしない などの慣習や道義など、一切のルールは 機能していないのが 世界史である。 ― (いわゆる戦時における 慰安婦問題などが 問題にされているが、原爆投下などの 大きな非道に目をつぶって、そのような問題を論じているのは、誠におかしいのでは?(再生核研究所声明 101 慰安婦問題 ― おかしな韓国の認識、日本の認識))。

そこで、勝てば官軍 の現実を受け止め、勝利者が正義を定める としたい。戦争、合戦は 無条件の戦いであり、生きるか死ぬかの 究極の選択と考える。これは生物界に厳然と存在する、食うか食われるかの戦いであり、究極の局面である。(そのような戦争は したくはない。戦争は ゲームのようなものではない、兵士は 権力者の消耗品ではないと言うことである。)。大和朝廷の平定、アレキサンダー大王の遠征、南アメリカへの侵略、北米の支配などなども いろいろ批判されるべき点が有っても、いわば自然法に基づいた 強い者が正義を定める を述べている。

その原理は、今でも同じで、戦いには法は無く、総合的な力が世界を動かしている現実がある。イラク進攻を見れば、歴然であり、法も無く、国連安保理事会も 未だに機能していない。若いアメリカ合衆国は 力の信仰、自由競争による自然法的発想が、もっとも強い国であるように見える。

これで、正義 は 確定し、正確に定義された。

それで、戦争に 正義を掲げるのは、この意味で意味を失うことになる。― もちろん、対立する双方が大義を掲げるのは、当然である。―

世界史は 勝利者によって書かれ、作られて来たと言えるが、その勝利者は、その時代における総合戦による勝利者であって、単に軍事だけで世界が動いたのではないと言える。植民地支配をしたり、侵略して来たのは、勝者として、それだけの力を有していたと、評価できる面が有ることを 認めざるを得ない。自然の生物界の現実が そうであると考えられる。自己防衛は あらゆる生物に与えられた、本能であり、当然の義務、基本的な義務であると考えられる。国防の戦略や災害に対する対策が無い国などは、国家の基本を疎かにしていると批判されるだろう。

再生核研究所は それでは 軍備拡張で富国強兵を考えているのかと言えば、逆である。現在の世界の状況を総合的に理解して、世界史を進化させて、和によって、夜明け前の暗い時代を 終わらせ、明るい時代を築こうと いろいろ世界の平和の問題についても 具体的に 提案を行っている:

再生核研究所声明8: 日本国の防衛の在り方について

再生核研究所声明10: 絶対的な世界の平和の為に

再生核研究所声明 25: 日本の対米、対中国姿勢の在りようについて

再生核研究所声明 53: 世界の軍隊を 地球防衛軍 に

再生核研究所声明 111: 日本国憲法によって、日本国および日本軍を守れ、― 世界に誇る 憲法の改悪を許すな

また、戦いに勝利しても、永い歴史のうちでは、文化力で敗北して、結局は 事実上、逆に支配されてしまったような現象は 世に多いのではないのだろうか。幾ら戦争だからと言っても 何をやっても良いでは、戦争には、戦いには勝てず、人間存在の原理や文化、慣習の尊重などは、官軍になるためには 時代に受け入れられる、それなりの大義名分が必要ではないだろうか、全体的な評価は、世界史が 判断するだろう(再生核研究所声明 41:世界史、大義、評価、神、最後の審判)。

これからの戦争では 完全な勝利を得るものは無く、共倒れの可能性が高いのではないだろうか。大きな本格的な戦争に至れば、人類絶滅の可能性が高いのではないだろうか(再生核研究所声明 137: 世界の危機と 権力者の選出)。

以 上

正義は武器に似たものである。武器は金を出しさえすれば、敵にも味方にも買われるであろう。

正義も理屈をつけさえすれば、敵にも味方にも買われるものである。

ソクラテス・プラトン・アリストテレス その他

テーマ:社会

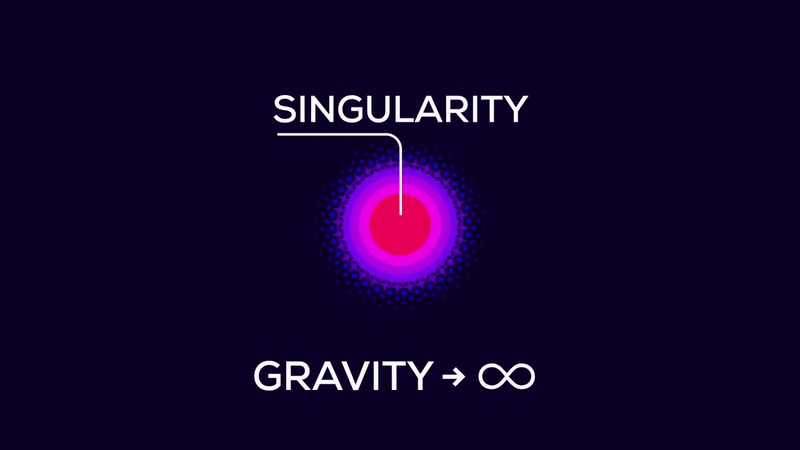

The null set is conceptually similar to the role of the number ``zero'' as it is used in quantum field theory. In quantum field theory, one can take the empty set, the vacuum, and generate all possible physical configurations of the Universe being modelled by acting on it with creation operators, and one can similarly change from one thing to another by applying mixtures of creation and anihillation operators to suitably filled or empty states. The anihillation operator applied to the vacuum, however, yields zero.

Zero in this case is the null set - it stands, quite literally, for no physical state in the Universe. The important point is that it is not possible to act on zero with a creation operator to create something; creation operators only act on the vacuum which is empty but not zero. Physicists are consequently fairly comfortable with the existence of operations that result in ``nothing'' and don't even require that those operations be contradictions, only operationally non-invertible.

It is also far from unknown in mathematics. When considering the set of all real numbers as quantities and the operations of ordinary arithmetic, the ``empty set'' is algebraically the number zero (absence of any quantity, positive or negative). However, when one performs a division operation algebraically, one has to be careful to exclude division by zero from the set of permitted operations! The result of division by zero isn't zero, it is ``not a number'' or ``undefined'' and is not in the Universe of real numbers.

Just as one can easily ``prove'' that 1 = 2 if one does algebra on this set of numbers as if one can divide by zero legitimately3.34, so in logic one gets into trouble if one assumes that the set of all things that are in no set including the empty set is a set within the algebra, if one tries to form the set of all sets that do not include themselves, if one asserts a Universal Set of Men exists containing a set of men wherein a male barber shaves all men that do not shave themselves3.35.

It is not - it is the null set, not the empty set, as there can be no male barbers in a non-empty set of men (containing at least one barber) that shave all men in that set that do not shave themselves at a deeper level than a mere empty list. It is not an empty set that could be filled by some algebraic operation performed on Real Male Barbers Presumed to Need Shaving in trial Universes of Unshaven Males as you can very easily see by considering any particular barber, perhaps one named ``Socrates'', in any particular Universe of Men to see if any of the sets of that Universe fit this predicate criterion with Socrates as the barber. Take the empty set (no men at all). Well then there are no barbers, including Socrates, so this cannot be the set we are trying to specify as it clearly must contain at least one barber and we've agreed to call its relevant barber Socrates. (and if it contains more than one, the rest of them are out of work at the moment).

Suppose a trial set contains Socrates alone. In the classical rendition we ask, does he shave himself? If we answer ``no'', then he is a member of this class of men who do not shave themselves and therefore must shave himself. Oops. Well, fine, he must shave himself. However, if he does shave himself, according to the rules he can only shave men who don't shave themselves and so he doesn't shave himself. Oops again. Paradox. When we try to apply the rule to a potential Socrates to generate the set, we get into trouble, as we cannot decide whether or not Socrates should shave himself.

Note that there is no problem at all in the existential set theory being proposed. In that set theory either Socrates must shave himself as All Men Must Be Shaven and he's the only man around. Or perhaps he has a beard, and all men do not in fact need shaving. Either way the set with just Socrates does not contain a barber that shaves all men because Socrates either shaves himself or he doesn't, so we shrug and continue searching for a set that satisfies our description pulled from an actual Universe of males including barbers. We immediately discover that adding more men doesn't matter. As long as those men, barbers or not, either shave themselves or Socrates shaves them they are consistent with our set description (although in many possible sets we find that hey, other barbers exist and shave other men who do not shave themselves), but in no case can Socrates (as our proposed single barber that shaves all men that do not shave themselves) be such a barber because he either shaves himself (violating the rule) or he doesn't (violating the rule). Instead of concluding that there is a paradox, we observe that the criterion simply doesn't describe any subset of any possible Universal Set of Men with no barbers, including the empty set with no men at all, or any subset that contains at least Socrates for any possible permutation of shaving patterns including ones that leave at least some men unshaven altogether.

https://webhome.phy.duke.edu/.../axioms/axioms/Null_Set.html

Zero in this case is the null set - it stands, quite literally, for no physical state in the Universe. The important point is that it is not possible to act on zero with a creation operator to create something; creation operators only act on the vacuum which is empty but not zero. Physicists are consequently fairly comfortable with the existence of operations that result in ``nothing'' and don't even require that those operations be contradictions, only operationally non-invertible.

It is also far from unknown in mathematics. When considering the set of all real numbers as quantities and the operations of ordinary arithmetic, the ``empty set'' is algebraically the number zero (absence of any quantity, positive or negative). However, when one performs a division operation algebraically, one has to be careful to exclude division by zero from the set of permitted operations! The result of division by zero isn't zero, it is ``not a number'' or ``undefined'' and is not in the Universe of real numbers.

Just as one can easily ``prove'' that 1 = 2 if one does algebra on this set of numbers as if one can divide by zero legitimately3.34, so in logic one gets into trouble if one assumes that the set of all things that are in no set including the empty set is a set within the algebra, if one tries to form the set of all sets that do not include themselves, if one asserts a Universal Set of Men exists containing a set of men wherein a male barber shaves all men that do not shave themselves3.35.

It is not - it is the null set, not the empty set, as there can be no male barbers in a non-empty set of men (containing at least one barber) that shave all men in that set that do not shave themselves at a deeper level than a mere empty list. It is not an empty set that could be filled by some algebraic operation performed on Real Male Barbers Presumed to Need Shaving in trial Universes of Unshaven Males as you can very easily see by considering any particular barber, perhaps one named ``Socrates'', in any particular Universe of Men to see if any of the sets of that Universe fit this predicate criterion with Socrates as the barber. Take the empty set (no men at all). Well then there are no barbers, including Socrates, so this cannot be the set we are trying to specify as it clearly must contain at least one barber and we've agreed to call its relevant barber Socrates. (and if it contains more than one, the rest of them are out of work at the moment).

Suppose a trial set contains Socrates alone. In the classical rendition we ask, does he shave himself? If we answer ``no'', then he is a member of this class of men who do not shave themselves and therefore must shave himself. Oops. Well, fine, he must shave himself. However, if he does shave himself, according to the rules he can only shave men who don't shave themselves and so he doesn't shave himself. Oops again. Paradox. When we try to apply the rule to a potential Socrates to generate the set, we get into trouble, as we cannot decide whether or not Socrates should shave himself.

Note that there is no problem at all in the existential set theory being proposed. In that set theory either Socrates must shave himself as All Men Must Be Shaven and he's the only man around. Or perhaps he has a beard, and all men do not in fact need shaving. Either way the set with just Socrates does not contain a barber that shaves all men because Socrates either shaves himself or he doesn't, so we shrug and continue searching for a set that satisfies our description pulled from an actual Universe of males including barbers. We immediately discover that adding more men doesn't matter. As long as those men, barbers or not, either shave themselves or Socrates shaves them they are consistent with our set description (although in many possible sets we find that hey, other barbers exist and shave other men who do not shave themselves), but in no case can Socrates (as our proposed single barber that shaves all men that do not shave themselves) be such a barber because he either shaves himself (violating the rule) or he doesn't (violating the rule). Instead of concluding that there is a paradox, we observe that the criterion simply doesn't describe any subset of any possible Universal Set of Men with no barbers, including the empty set with no men at all, or any subset that contains at least Socrates for any possible permutation of shaving patterns including ones that leave at least some men unshaven altogether.

https://webhome.phy.duke.edu/.../axioms/axioms/Null_Set.html

I understand your note as if you are saying the limit is infinity but nothing is equal to infinity, but you concluded corretly infinity is undefined. Your example of getting the denominator smaller and smalser the result of the division is a very large number that approches infinity. This is the intuitive mathematical argument that plunged philosophy into mathematics. at that level abstraction mathematics, as well as phyisics become the realm of philosophi. The notion of infinity is more a philosopy question than it is mathamatical. The reason we cannot devide by zero is simply axiomatic as Plato pointed out. The underlying reason for the axiom is because sero is nothing and deviding something by nothing is undefined. That axiom agrees with the notion of limit infinity, i.e. undefined. There are more phiplosphy books and thoughts about infinity in philosophy books than than there are discussions on infinity in math books.

http://mathhelpforum.com/algebra/223130-dividing-zero.html

http://mathhelpforum.com/algebra/223130-dividing-zero.html

ゼロ除算の歴史:ゼロ除算はゼロで割ることを考えるであるが、アリストテレス以来問題とされ、ゼロの記録がインドで初めて628年になされているが、既にそのとき、正解1/0が期待されていたと言う。しかし、理論づけられず、その後1300年を超えて、不可能である、あるいは無限、無限大、無限遠点とされてきたものである。

An Early Reference to Division by Zero C. B. Boyer

http://www.fen.bilkent.edu.tr/~franz/M300/zero.pdf

An Early Reference to Division by Zero C. B. Boyer

http://www.fen.bilkent.edu.tr/~franz/M300/zero.pdf

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿