Seeing the Sublime in Mathematics

Fine Art Images / Heritage Images / Getty

April 27, 2018 03:20 AM

Euler’s identity: Genius, discovery, elegance.

David Stipp’s short book, A Most Elegant Equation , aims to persuade the “math-averse” that “great mathematics is as provocative, beautiful, and deep as great art or literature.” His exemplar is Euler’s identity, which can be written as the gnomic formula eiπ + 1 = 0. Stipp offers to explain what it means, why it’s true, and why it is significant as science and as art. The discussion, he says, will take pains to assume no mathematical prerequisites beyond checkbook arithmetic, and he isn’t kidding. For example, every algebraic manipulation that crops up is accompanied by a verbal paraphrase (often lengthy). A 101-word footnote on page 15 is devoted to explaining why “x = −1” means the same thing as “x + 1 = 0.”

“Euler” is Leonhard Euler, the master mathematician of the 18th century and one of the greatest of all time—also the most prolific. Publication of his collected works, begun in 1911 and ongoing, will total more than 80 large volumes. He is by all accounts an appealing character—a pious family man who, according to one contemporary, could work happily with “a child on his knees, a cat on his back.” Euler was generous in his dealings with other scholars, a good teacher, and something of a polymath who, in addition to his native German, knew Latin, Russian, French, and English and published works on mathematics, science, philosophy, and music. He could recite the entire Aeneid from memory. Euler began to lose his sight at an early age but blindness seemed if anything to increase his productivity: He worked things out in his head and dictated the results.

An ordinary genius is a fellow you and I would be just as good as, if we were only many times better. . . . It is different with the magicians . . . the working of their minds is for all intents and purposes incomprehensible.

The exotic ingredient in Euler’s identity is eiπ: π is what you think, the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter; eand i need considerable explaining, as does the use of iπ as an exponent (“raising e to the power iπ”). Without rehearsing those lengthy explanations it’s possible to scan the terrain in which that intellectual adventure takes place.

To begin concretely, but not too helpfully, e is a number a bit greater than 2.7. Like π, it cannot be expressed as a decimal that stops or settles into a repetitive pattern, and it crops up everywhere in mathematics, physics, and engineering (among other places). To go further we must expand our minds to accept the idea of carrying out operations, such as addition, infinitely often. Here’s a very simple example: Imagine a stool that stands on a single post that’s one foot long. Chop off the post’s bottom half (leaving 1/2 foot); chop off half of what’s left (so you’ve now chopped off 1/2 + 1/4, leaving 1/4); chop off half of what’s left (you’ve now chopped off 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8, leaving 1/8); carry on as long as you like. Any point on the post can be chopped off by carrying on long enough. If one could somehow finish performing all of the infinitely many chops the entire post would be consumed; the seat of the stool would lie on the floor. So it’s tempting to say that we can meaningfully add together all the infinitely many lengths that were chopped off and that the resulting sum must total the one-foot length that was consumed:

1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + . . . = 1

(The “. . .” means “You get the idea; go on like this forever.”) One might say that, if only to seem mysterious and clever, but why bother? Because deploying infinite operations and manipulating them by something like the ordinary rules of algebra is a powerful way to solve old problems and discover new truths—including truths, like Euler’s identity, that don’t explicitly refer to infinities. Euler displayed his virtuosity with these methods in Introduction to the Analysis of the Infinite , perhaps the most influential mathematics textbook since Euclid’s. Another century of work was needed to put them on sound logical footing and avoid lurking fallacies and errors. Meanwhile, Euler’s imagination (or chutzpah)—guided by a deep, if not quite infallible, intuition—expanded the boundaries of mathematics.

Coming to grips with i requires overcoming a regrettable piece of terminology too old to change: “imaginary number.” i is called “imaginary” because it is assumed, by fiat, to satisfy the equation i×i = −1, even though none of the numbers we’re used to—now to be called, by contrast, “real” numbers—can possibly fill that bill: The result of multiplying a negative number by itself, or a positive number by itself, is always positive, so can’t equal −1. Thus, i is neither positive nor negative, but is still somehow something. As early as the 16th century, procedures for solving equations gave rise to expressions that, if they meant anything at all, could only denote such “imaginary” entities. They were embarrassments but could not simply be shunned: Faith-based persistence, applying the usual algebraic rules (and replacing i×i, when convenient, with −1), sometimes caused the unwanted expressions to drop out, leaving the “real” answers originally sought. Far from avoiding imaginaries, Euler exploited them with glee, opening up whole new mathematical vistas. Subsequent work has developed a logical foundation for the entire domain of complex numbers, those—such as 2, 3i, e+πi—that result from applying the operations of arithmetic to real and imaginary numbers.

What about eiπ? Those who remember high school algebra will recall that e2 means e×e (multiply two copies of e), that e3 means e×e×e, etc. But this hardly helps make sense of eiπ. What could “iπ copies of e” possibly mean? Euler proceeds by first finding an infinite sum that gives a formula for computing ex. That is, it computes e2 if we replace the infinitely many xs in the formula by 2, e3 if we replace them by 3, etc. He then declares that the meaning of eiπ is the result of replacing them all with iπ. Which is obvious if you’re the sort who can pioneer “analysis of the infinite” and the theory of complex numbers—and can, along the way, extend infinite analysis to complex numbers. Stipp quotes the 20th-century mathematician Mark Kac: “An ordinary genius is a fellow you and I would be just as good as, if we were only many times better. . . . It is different with the magicians . . . the working of their minds is for all intents and purposes incomprehensible.” Euler was a magician.

It unsettles ordinary mortals to follow rules without an account of what the rules are about, to accept without proof their internal consistency, and to trust that results about the real numbers reached by calculations that detour through the complex domain are true. Stipp’s next-to-last chapter sketches a modern representation of complex numbers as points in a two-dimensional plane. The “real” numbers lie along one straight line in that plane; another, perpendicular to it, contains the purely “imaginary” numbers. Arithmetic operations have a simple geometric meaning, as does Euler’s identity. Stipp’s account of all this seems pitched just right, a few worked examples that give a satisfying sense of how everything hangs together.

The final chapter, called “The Meaning of It All,” asks what makes it beautiful. Stipp begins by noting qualities that mathematicians have attributed to beautiful results. From G. H. Hardy, for example, he gets this famous list: seriousness, generality, depth, unexpectedness, inevitability, and economy. Such reflections will help those who already sense beauty in mathematics to articulate their experience; they won’t persuade others that beauty is there to be found. But persuasion is not Stipp’s aim. His book is not a work of philosophy. What he offers amounts not to an argument but to an experience, especially “the feeling of exaltation that we get from an encounter with an example of our species outdoing itself.” He trusts that someone who manages to “get” a beautiful result will recognize a kinship between that experience and the rewards provided by works of other kinds of art. Stipp’s prose can be overripe—in Euler’s identity, he writes, e, i, and π “react together to carve out a wormhole that spirals through the infinite depths of number space to emerge smack dab in the heartland of integers”—but he gives his reader a good shot at getting hold of something beautiful.https://www.weeklystandard.com/david-guaspari/seeing-the-sublime-in-mathematics

とても興味深く読みました:

ゼロ除算の発見と重要性を指摘した:日本、再生核研究所

再生核研究所声明343(2017.1.10)オイラーとアインシュタイン

世界史に大きな影響を与えた人物と業績について

再生核研究所声明314(2016.08.08) 世界観を大きく変えた、ニュートンとダーウィンについて

再生核研究所声明315(2016.08.08) 世界観を大きく変えた、ユークリッドと幾何学

再生核研究所声明339(2016.12.26)インドの偉大な文化遺産、ゼロ及び算術の発見と仏教

で 触れてきたが、興味深いとして 続けて欲しいとの希望が寄せられた。そこで、ここでは、数学界と物理学界の巨人 オイラーとアインシュタインについて触れたい。

オイラーが膨大な基本的な業績を残され、まるでモーツァルトのように 次から次へと数学を発展させたのは驚嘆すべきことであるが、ここでは典型的で、顕著な結果であるいわゆるオイラーの公式 e^{\pi i} = -1 を挙げたい。これについては相当深く纏められた記録があるので参照して欲しい(

)。この公式は最も基本的な数、-1,\pi, e,i の簡潔な関係を確立しており、複素解析や数学そのものの骨格の中枢の関係を与えているので、世界史への甚大なる影響は歴然である ― オイラーの公式 (e ^{ix} = cos x + isin x) を一般化として紹介できます。 そのとき、数と角の大きさの単位の関係で、神は角度を数で測っていることに気付く。左辺の x は数で、右辺の x は角度を表している。それらが矛盾なく意味を持つためには角は、角の 単位は数の単位でなければならない。これは角の単位を 60 進法や 10 進法などと勝手に決められないことを述べている。ラジアンなどの用語は不要であることが分かる。これが神様方式による角の単位です。角の単位が数ですから、そして、数とは複素数ですから、複素数 の三角関数が考えられます。cos i も明確な意味を持ちます。このとき、たとえば、純虚数の 角の余弦関数が電線をぶらりとたらした時に描かれる、けんすい線として、実際に物理的に 意味のある美しい関数を表現します。そこで、複素関数として意味のある雄大な複素解析学 の世界が広がることになる。そしてそれらは、数学そのものの基本的な世界を構成すること になる。自然の背後には、神の設計図と神の意思が隠されていますから、神様の気持ちを理解し、 また神に近付くためにも、数学の研究は避けられないとなると思います。数学は神学そのものであると私は考える。オイラーの公式の魅力は千年や万年考えても飽きることはなく、数学は美しいとつぶやき続けられる。― 特にオイラーの公式は、言わば神秘的な数、虚数i、―1, e、\pi などの明確な意味を与えた意義は 凄いこととであると驚嘆させられる。

次に アインシュタインであるが、いわゆる相対性理論として、物理学界の最高峰に存在するが、アインシュタインの公式 E=mc^2 は素人でもびっくりする 簡潔で深い結果である。何と物質はエネルギーと等式で結ばれるという。このような公式の発見は人類の名誉に関わる基本的な結果と考えられる。アインシュタインが、時間、空間、物質、エネルギー、光速の基本的な関係を確立し、現代物理学の基礎を確立している。

ところで、上記巨人に共通する面白い話題が存在する。 オイラーがゼロ除算を記録に残し 1/0=\infty と記録し、広く間違いとして指摘されている。 他方、 アインシュタインは次のように述べている:

Blackholes are where God divided by zero. I don't believe in mathematics.

George Gamow (1904-1968) Russian-born American nuclear physicist and cosmologist remarked that "it is well known to students of high school algebra" that division by zero is not valid; and Einstein admitted it as {\bf the biggest blunder of his life} (

Gamow, G., My World Line (Viking, New York). p 44, 1970).

今でも、この先を、特に特殊相対性理論との関係で 0/0=1 であると頑強に主張したり、想像上の数と考えたり、ゼロ除算についていろいろな説が存在して、混乱が続いている。

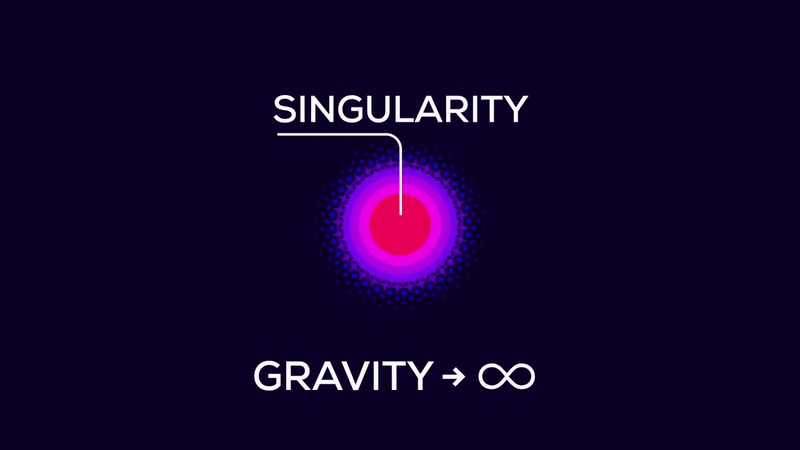

しかしながら、ゼロ除算については、決定的な結果を得た と公表している。すなわち、分数、割り算は自然に一意に拡張されて、 1/0=0/0=z/0=0 である。無限遠点は 実はゼロで表される:

The division by zero is uniquely and reasonably determined as 1/0=0/0=z/0=0 in the natural extensions of fractions. We have to change our basic ideas for our space and world:

Division by Zero z/0 = 0 in Euclidean Spaces

Hiroshi Michiwaki, Hiroshi Okumura and Saburou Saitoh

International Journal of Mathematics and Computation Vol. 28(2017); Issue 1, 2017), 1-16.

http://www.scirp.org/journal/alamt http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/alamt.2016.62007

http://www.ijapm.org/show-63-504-1.html

http://www.diogenes.bg/ijam/contents/2014-27-2/9/9.pdf

http://www.ijapm.org/show-63-504-1.html

http://www.diogenes.bg/ijam/contents/2014-27-2/9/9.pdf

Announcement 326: The division by zero z/0=0/0=0 - its impact to human beings through education and research

以 上

再生核研究所声明347(2017.1.17) 真実を語って処刑された者

まず歴史的な事実を挙げたい。Pythagoras、紀元前582年 - 紀元前496年)は、ピタゴラスの定理などで知られる、古代ギリシアの数学者、哲学者。彼の数学や輪廻転生についての思想はプラトンにも大きな影響を与えた。「サモスの賢人」、「クロトンの哲学者」とも呼ばれた(ウィキペディア)。辺の長さ1の正方形の対角線の長さが ル-ト2であることがピタゴラスの定理から導かれることを知っていたが、それが整数の比で表せないこと(無理数であること)を発見した弟子Hippasusを 無理数の世界観が受け入れられないとして、その事実を隠したばかりか、その事実を封じるために弟子を殺してしまったという。

また、ジョルダーノ・ブルーノ(Giordano Bruno, 1548年 - 1600年2月17日)は、イタリア出身の哲学者、ドミニコ会の修道士。それまで有限と考えられていた宇宙が無限であると主張し、コペルニクスの地動説を擁護した。異端であるとの判決を受けても決して自説を撤回しなかったため、火刑に処せられた。思想の自由に殉じた殉教者とみなされることもある。彼の死を前例に考え、轍を踏まないようにガリレオ・ガリレイは自説を撤回したとも言われる(ウィキペディア)。

さらに、新しい幾何学の発見で冷遇された歴史的な事件が想起される:

非ユークリッド幾何学の成立

ニコライ・イワノビッチ・ロバチェフスキーは「幾何学の新原理並びに平行線の完全な理論」(1829年)において、「虚幾何学」と名付けられた幾何学を構成して見せた。これは、鋭角仮定を含む幾何学であった。

ボーヤイ・ヤーノシュは父・ボーヤイ・ファルカシュの研究を引き継いで、1832年、「空間論」を出版した。「空間論」では、平行線公準を仮定した幾何学(Σ)、および平行線公準の否定を仮定した幾何学(S)を論じた。更に、1835年「ユークリッド第 11 公準を証明または反駁することの不可能性の証明」において、Σ と S のどちらが現実に成立するかは、如何なる論理的推論によっても決定されないと証明した(ウィキペディア)。

知っていて、科学的な真実は人間が否定できない事実として、刑を逃れるために妥協したガリレオ、世情を騒がせたくない、自分の心をそれ故に乱したくない として、非ユークリッド幾何学について 相当な研究を進めていたのに 生前中に公表をしなかった数学界の巨人 ガウスの処世を心に留めたい。

ピタゴラス派の対応、宗教裁判における処刑、それらは、真実よりも権威や囚われた考えに固執していたとして、誠に残念な在り様であると言える。非ユークリッド幾何学の出現に対する風潮についても2000年間の定説を覆す事件だったので、容易には理解されず、真摯に新しい考えの検討すらしなかったように見える。

真実を、真理を求めるべき、数学者、研究者、宗教家のこのような態度は相当根本的におかしいと言わざるを得ない。実際、人生の意義は帰するところ、真智への愛にあるのではないだろうか。本当のこと、世の中のことを知りたいという愛である。顕著な在り様が研究者や求道者、芸術家達ではないだろうか。そのような人たちの過ちを省みて自戒したい: 具体的には、

1) 新しい事実、現象、考え、それらは尊重されるべきこと。多様性の尊重。

2) 従来の考えや伝統に拘らない、いろいろな考え、見方があると柔軟に考える。

3) もちろん、自分たちの説に拘ったりして、新しい考え方を排除する態度は恥ずべきことである。どんどん新しい世界を拓いていくのが人生の基本的な在り様であると心得る。

4) もちろん、自分たちの流派や組織の利益を考えて新規な考えや理論を冷遇するのは真智を愛する人間の恥である。

5) 巨人、ニュートンとライプニッツの微積分の発見の先取争いに見られるような過度の競争意識や自己主張は、浅はかな人物に当たるとみなされる。真智への愛に帰するべきである。

数学や科学などは 明確に直接個々の人間にはよらず、事実として、人間を離れて存在している。従って無理数も非ユークリッド幾何学も、地球が動いている事も、人間に無関係で そうである事実は変わらない。その意味で、多数決や権威で結果を決めようとしてはならず、どれが真実であるかの観点が決定的に大事である。誰かではなく、真実はどうか、事実はどうかと真摯に、真理を追求していきたい。

人間が、人間として生きる究極のことは、真智への愛、真実を知りたい、世の中を知りたい、神の意思を知りたいということであると考える。 このような観点で、上記世界史の事件は、人類の恥として、このようなことを繰り返さないように自戒していきたい(再生核研究所声明 41(2010/06/10): 世界史、大義、評価、神、最後の審判)。

以 上

再生核研究所声明 411(2018.02.02): ゼロ除算発見4周年を迎えて

ゼロ除算100/0=0を発見して、4周年を迎える。 相当夢中でひたすらに その真相を求めてきたが、一応の全貌が見渡せ、その基礎と展開、相当先も展望できる状況になった。論文や日本数学会、全体講演者として招待された大きな国際会議などでも発表、著書原案154ページも纏め(http://okmr.yamatoblog.net/)基礎はしっかりと確立していると考える。数学の基礎はすっかり当たり前で、具体例は700件を超え、初等数学全般への影響は思いもよらない程に甚大であると考える: 空間、初等幾何学は ユークリッド以来の基本的な変更で、無限の彼方や無限が絡む数学は全般的な修正が求められる。何とユークリッドの平行線の公理は成り立たず、すべての直線は原点を通るというが我々の数学、世界であった。y軸の勾配はゼロであり、\tan(\pi/2) =0 である。 初等数学全般の修正が求められている。

数学は、人間を超えたしっかりとした論理で組み立てられており、数学が確立しているのに今でもおかしな議論が世に横行し、世の常識が間違っているにも拘わらず、論文発表や研究がおかしな方向で行われているのは 誠に奇妙な現象であると言える。ゼロ除算から見ると数学は相当おかしく、年々間違った数学やおかしな数学が教育されている現状を思うと、研究者として良心の呵責さえ覚える。

複素解析学では、無限遠点はゼロで表されること、円の中心の鏡像は無限遠点では なくて中心自身であること、ローラン展開は孤立特異点で意味のある、有限確定値を取ることなど、基本的な間違いが存在する。微分方程式などは欠陥だらけで、誠に恥ずかしい教科書であふれていると言える。 超古典的な高木貞治氏の解析概論にも確かな欠陥が出てきた。勾配や曲率、ローラン展開、コーシーの平均値定理さえ進化できる。

ゼロ除算の歴史は、数学界の避けられない世界史上の汚点に成るばかりか、人類の愚かさの典型的な事実として、世界史上に記録されるだろう。この自覚によって、人類は大きく進化できるのではないだろうか。

そこで、我々は、これらの認知、真相の究明によって、数学界の汚点を解消、世界の文化への貢献を期待したい。

ゼロ除算の真相を明らかにして、基礎数学全般の修正を行い、ここから、人類への教育を進め、世界に貢献することを願っている。

ゼロ除算の発展には 世界史がかかっており、数学界の、社会への対応をも 世界史は見ていると感じられる。 恥の上塗りは世に多いが、数学界がそのような汚点を繰り返さないように願っている。

人の生きるは、真智への愛にある、すなわち、事実を知りたい、本当のことを知りたい、高級に言えば神の意志を知りたいということである。そこで、我々のゼロ除算についての考えは真実か否か、広く内外の関係者に意見を求めている。関係情報はどんどん公開している。

4周年、思えば、世の理解の遅れも反映して、大丈夫か、大丈夫かと自らに問い、ゼロ除算の発展よりも基礎に、基礎にと向かい、基礎固めに集中してきたと言える。それで、著書原案ができたことは、楽しく充実した時代であったと喜びに満ちて回想される。

以 上

List of division by zero:

\bibitem{os18}

H. Okumura and S. Saitoh,

Remarks for The Twin Circles of Archimedes in a Skewed Arbelos by H. Okumura and M. Watanabe, Forum Geometricorum.

Saburou Saitoh, Mysterious Properties of the Point at Infinity、

arXiv:1712.09467 [math.GM]

arXiv:1712.09467 [math.GM]

Hiroshi Okumura and Saburou Saitoh

The Descartes circles theorem and division by zero calculus. 2017.11.14

L. P. Castro and S. Saitoh, Fractional functions and their representations, Complex Anal. Oper. Theory {\bf7} (2013), no. 4, 1049-1063.

M. Kuroda, H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh, and M. Yamane,

New meanings of the division by zero and interpretations on $100/0=0$ and on $0/0=0$, Int. J. Appl. Math. {\bf 27} (2014), no 2, pp. 191-198, DOI: 10.12732/ijam.v27i2.9.

T. Matsuura and S. Saitoh,

Matrices and division by zero z/0=0,

Advances in Linear Algebra \& Matrix Theory, 2016, 6, 51-58

Published Online June 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/alamt

\\ http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/alamt.2016.62007.

T. Matsuura and S. Saitoh,

Division by zero calculus and singular integrals. (Submitted for publication).

T. Matsuura, H. Michiwaki and S. Saitoh,

$\log 0= \log \infty =0$ and applications. (Differential and Difference Equations with Applications. Springer Proceedings in Mathematics \& Statistics.)

H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh and M.Yamada,

Reality of the division by zero $z/0=0$. IJAPM International J. of Applied Physics and Math. 6(2015), 1--8. http://www.ijapm.org/show-63-504-1.html

H. Michiwaki, H. Okumura and S. Saitoh,

Division by Zero $z/0 = 0$ in Euclidean Spaces,

International Journal of Mathematics and Computation, 28(2017); Issue 1, 2017), 1-16.

H. Okumura, S. Saitoh and T. Matsuura, Relations of $0$ and $\infty$,

Journal of Technology and Social Science (JTSS), 1(2017), 70-77.

S. Pinelas and S. Saitoh,

Division by zero calculus and differential equations. (Differential and Difference Equations with Applications. Springer Proceedings in Mathematics \& Statistics).

S. Saitoh, Generalized inversions of Hadamard and tensor products for matrices, Advances in Linear Algebra \& Matrix Theory. {\bf 4} (2014), no. 2, 87--95. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ALAMT/

S. Saitoh, A reproducing kernel theory with some general applications,

Qian,T./Rodino,L.(eds.): Mathematical Analysis, Probability and Applications - Plenary Lectures: Isaac 2015, Macau, China, Springer Proceedings in Mathematics and Statistics, {\bf 177}(2016), 151-182. (Springer) .

2018.3.18.午前中 最後の講演: 日本数学会 東大駒場、函数方程式論分科会 講演書画カメラ用 原稿

The Japanese Mathematical Society, Annual Meeting at the University of Tokyo. 2018.3.18.

https://ameblo.jp/syoshinoris/entry-12361744016.html より

The Japanese Mathematical Society, Annual Meeting at the University of Tokyo. 2018.3.18.

https://ameblo.jp/syoshinoris/entry-12361744016.html より

*057 Pinelas,S./Caraballo,T./Kloeden,P./Graef,J.(eds.):

Differential and Difference Equations with Applications:

ICDDEA, Amadora, 2017.

(Springer Proceedings in Mathematics and Statistics, Vol. 230)

May 2018 587 pp.

再生核研究所声明 425(2018.4.28): 生命のリズム、生きること

(学会、著作、解説などに気をとられ 声明の方は珍しく空けてしまった。待っているような状況も存在したが、しばらく間を取るのが良いような気持も、年度の変わり目の要素もあり、他方、豊かな自然の季節の変化の大きさに驚かされたりしてもいた。 ふと、人生の在り様、心の微妙さを表現してみたい気持ちが湧いてきた。最初の感じは悟りの心得であったが、幾らなんでもその題名は適当ではないようにその心の背景から感じて題名を表記のように書き、書き始めた。)

まず、修業、悟りの方向とは、凡そ世の過程はゼロから始まってゼロに帰する、したがってゼロに帰することを受け入れる気持ちを持つことが悟り、修業の方向であると 相当に考えを抱いてきた(夜明け前 - よっちゃんの想い 文芸社)。ところが一向に悟りは進まず、逆に煩悩がどんどん湧いてくるような反作用が働いている面も感じられてくる。年齢相当に、成功しても、失敗してもどちらでもよい、所詮大したことはない、 失敗すればかえって面白い、初期に戻っても、進んでも結局みな同じようになるので、何も拘ることはないという自由な気持ちも素直に受け入れられる気持ちになっている。そうすると世の中 人の営みが結構、幼稚におかしく見えてくる。人間社会も野生動物の世界も同じようで、調和のとれている野生生物の世界の方が完全な営みに見えて来る。人間社会の愚かしさと いい加減さには浅ましさより、いとおしささえ感じられてしまう。- 超大国の大統領が恥じらいもなく、アメリカファーストと公言されているのですから、凄いですね。核兵器を苦労して開発して、今度は廃棄するから、援助をお願いしたい。余りにも古い論理、考え方が続いているおかしさ。日本では、大事な国の問題よりセクハラや忖度問題で騒いでいるおめでたい世相。

悟りの方向として、無を受け入れる、元に戻ることを受け入れる修行、己を空しゅうする心構えを身につける。それらが正道と思われるが、それに対して、活動している、発展している心をリズムにのって未来未来と上手く展開していくのは 生命の充実として 良い在りようではないだろうか。どんどん生きていくということである。生きるということはもちろん、生物的な本能を満たし、創造的な活動を続けていくことである。良い感動は良い創造活動にあるのではないだろうか。

また良い創造を共感、共鳴することも人間存在の本質的な歓びに属するのではないだろうか。人の心は多様であり、人の志、心の在りようも多様であるから、何事も同じようには考えられず、帰するところは個人、個人が 良い思いを、感動するにはどうしたら良いかとなるが、これらは自分の心の総体をしっかりと捉え、環境の中で上手く調和させて行く心掛けが大事ではないだろうか。人はあまりにも周りのことに気遣いをし過ぎで肝心な自分をないがしろにしている現実があるように感じられるが如何であろうか。

人間の心は、極めて微妙で、変化を求め、どんどん変化している。その背後にあるものをしっかりと捉えようとし、さらにその方向の様子、ペースなどもしっかり捉えて、全体の調和ある在りようを志向して行きたい。岡本太郎氏の 芸術は爆発だ どんどん爆発して行けば良いは 確かにそうではないだろうか。 前向きにどんどん進んでいるとき、生命の充実が感じられる。それは悟りの他の方向とも言えるのではないだろうか。どんな過去の想い出も、足跡も空しく、前向きに進んでいるときこそが 充実感を覚えるときであると言える。

以 上

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿