Relativity: Final ascent of physics

Since 2007, physicist Leonard Susskind has regularly delivered a lecture series called the Theoretical Minimum, on the foundations needed to study different areas of physics (http://theoreticalminimum.com/home). Companion volumes have emerged, the first on classical mechanics and the second on quantum mechanics. Special Relativity and Classical Field Theoryis the third and final volume. Like the book on quantum mechanics, it is co-authored by Art Friedman and aimed, in Susskind's words, at “physics enthusiasts” or “people who know, or once knew, a bit of algebra and calculus, but are more or less beginners”.

The latest volume concerns the strange world that Albert Einstein discovered by combining James Clerk Maxwell's field theory with Isaac Newton's mechanics — a world in which moving fast makes time compress and lengths shorten. To understand it, challenging mathematical tools are required. In this volume, as in the others, you get the sense of being led up a legendary mountain by a trained guide. The guide knows you are an amateur, but wants you to get to the top on your own, without being airlifted over risky terrain. You do not hike through some of the hardest passes or peaks, nor past some of the most magnificent vistas. It's a peculiar route, and you encounter many sites in a different order from the one early explorers adopted, or in the way experts are used to teaching. But it's accessible. And you do get to the top. As an amateur myself, I found it thrilling.

The path starts with the first lecture, a discussion of reference frames. These are tools for labelling the positions of objects in your immediate space, and in spaces moving with respect to yours (such as on a train), that allow you to go back and forth between the spaces. Understanding them is an important skill for traversing rough spots ahead. Other essential tools include space-time, in which the reference frame includes time as well as space; proper time; and four-vectors, special kinds of paths and objects in space-time.

In a book on special relativity, you might expect to meet Einstein's mass–energy equivalence, E = mc2, close to the beginning. Yet you don't encounter it until Lecture 3, about 100 pages in, where it is refreshingly derived from first principles. You don't get the important Euler–Lagrange equation, which describes particle motion, until Lecture 4. Poisson's equation, for the electrostatic potential of a particle, and the Klein–Gordon equation, which describes a particle as a wave and relativistically, don't show up until Lecture 5. Gauge invariance, the basis of modern field theory, appears first in Lecture 7; Maxwell's equations, which provide the foundation of classical electromagnetism, materialize in Lecture 8; and the Poynting vector, which describes the flow of energy in electromagnetic waves, surfaces first in Lecture 11.

From a historian's point of view, therefore, the path is topsy-turvy. But Susskind's approach is to subject the novice to a historical mathematical boot camp to make the path seem natural, and ultimately easier.

He appeals to the reader's evolving understanding to stay motivated, rather than airing his own expertise. Whenever you are puzzled by the famous conundrums of special relativity — the twin paradox, for instance, in which a sibling journeying on a light-speed rocket ages less than one who stays at home — he instructs you to “draw a spacetime diagram”. Such visual representations, he notes, make most of the weirdness in relativistic events go away.

Friedman pops up as the most vocal hiker on this at-times steep slope. He is not averse to making protests: “I don't recognize any of this. I thought you said we were going to get the Lorentz force law.” (“Lenny” replies: “Hang on, Art, we're getting there.”) Such jousts are infrequent, yet preserve the book's informal tone. In that vein, the narrative is rich in remarks at once witty and insightful. Modifying physicist John Wheeler's quote on relativity — “space-time tells matter how to move; matter tells space-time how to curve” — Susskind remarks, “Fields tell charges how to move; charges tell fields how to vary.”

Understanding the theoretical minimum in special relativity and classical field theory, however, itself demands a certain minimum of preparation and research. The book occasionally bumps up against this problem, referring the reader to earlier volumes; or Susskind might impatiently write, “If you don't know what a cross product is, please take the time to learn.”

The last few chapters are the steepest. You meet landmarks that would have been encountered much earlier in a historical approach, such as the laws of Maxwell, Charles de Coulomb, André-Marie Ampère and Michael Faraday — and even Maxwell's discovery that light is composed of electromagnetic waves, not mentioned until close to the end. But these conclusions fall right out of the tools you have been given in your intensive training — which Susskind calls the “cold shower” approach.

So why buy the book when the lectures are online? The online course consists of ten lectures, each anywhere up to two hours long, whereas the book is orderly and concise. You can go at your own pace, make notes and appreciate where Friedman — a former student of the course — becomes your stand-in and asks the questions that nag at you. You can refer back to something you read earlier and locate it quickly, rather than try to remember how far into the lecture it was and skip around until you find it. Finishing the book, you the physics enthusiast may not have a more profound view of any particular landmark in physics than before. But you will surely have a much more reliable map of the territory.

とても興味深く読みました:

再生核研究所声明 383 (2017.9.18): 人間の精神の高まりについての視点

題名の正確な意味の表現は難しい。そこで、具体的な例を挙げて意図していることをより明らかにしよう。

小学生時代を回想しよう。 低学年ではどんどん世界が広がっていくようで、知識も情報も世界も段々、どんどん広がりどんどん世界が見えるようになっていくと感じられるだろう。 それと同時に 過去の自分の様、様子が良く見える、分かる様に感じられるだろう。 このような現象は、登山でどんどん登って行くと視野が開けて、辿ってきた様、情景がすっかり見え全体の様子が分かるような経験にもみられる。このような事は旅行で ある小さな町を訪れ、滞在しているにつれて 町全体の様子が段々分かってきて、町全体をあるイメージで捉えられるようになるだろう。最初の段階で戸惑っていた自分を知ることが出来るだろう。これらの現象は様様の研究や学問、芸術、修業等についてもみられるといえる。― ある意味での進化である。 ここでは、そのような現象を、登山の例から 人間精神の高まりと表現した。正確な表現は心の問題であるから難しい。大きな特徴は段々今までの状況を含むような形で、知識や情報が拡大して、心も質的に変化して以前の状況をより広い視点から捉えられるように成長、進んでいることである。

人生とは何か、人間とは何かの基本的な 方向として、この意味における人間の精神の高まりがあると考えられる。逆に考えてみれば、知識や情報が拡大し、精神の高まりがなければ、必ず、停滞、退屈になり、そのような生活には飽きて、生き生きした人生にはならないのではないだろうか。人間、生物的な 本能的な欲求がある程度満たされれば、必ず、情報や知識を欲求し、やがて神の意思を知りたいという真智への愛に至るのではないだろうか。 この過程にみられる、人間の精神の高まり の様子、 状況に関心を持つ。

人間は真理を追究し、情報、知識の増大方向で進むが どんどん山頂を目指して進む時、 我々の精神全体はどのように変化していくであろうか、人間とはどのように成長していくであろうか。 数学界の天才、ニュートンとライプニッツは 生涯微積分学の発見の先駆者たるを主張して、裁判闘争を続けていたという、お粗末とも言える、事実が存在する。他方、精神の高まりを象徴する用語として、人物たる人物、人格者、覚者、賢人、悟りの境地、聖人などの理想を表す概念が存在する。― 人類自身、全体があたかも子供たちである様に見えてしまう進化した人間を想定すると慄然とするだろう。人生、世界、人類さえみえてしまう者の存在、思い当たる人として お釈迦様などが考えられよう。

ゼロ除算の発見で、人生とはゼロから始まり、何かが拡大を続け、やがて突然にゼロに帰すると表現した。この拡大は 正確には何を意味するであろうか。知識や情報、経験の増大は基本的であるが、覚性度なども気になる要素ではないだろうか。どんどん気づき、世界がどんどん見えてくる面である。

人生、精神的な高まりを通して成人を迎え、円熟期を迎えるが、人間の成長の理想的な境地とは何であろうか。知識を沢山集めてものしりになったり、どんどん発見や発明を続けていけば良いのだろうか。沢山良いものを発見したり、発明していけば良いのだろうか。

人間とは どのように作られているのかと 問う。― 人間存在の意義を求めている。

ある山頂に達して、人生、世界とは そのようなものであるとの見識に達した時、その心情のいろいろな在り様と いろいろな差は どのように解釈されるべきであろうか?

良き、人間とは、人生とはどのようなものであろうか?

― しかしながら、人生における基本定理、 人生の意義は感動することにある はそのような思考の基本になるのではないだろうか。

以 上

再生核研究所声明 382 (2017.9.11): ニュートンを越える天才たちに-育成する立場の人に

次のような文書を残した: いま思いついたこと:ニュートンは偉く、ガウス、オイラーなども 遥かに及ばないと 何かに書いてあると言うのです。それで、考え、思いついた。 ガウス、オイラーの業績は とても想像も出来なく、如何に基本的で、深く、いろいろな結果がどうして得られたのか、思いもよらない。まさに天才である。数学界にはそのような天才が、結構多いと言える。しかるに、ニュートンの業績は 万有引力の法則、運動の法則、微積分学さえ、理解は常人でも出来き、多くの数学上の結果もそうである。しかるにその偉大さは 比べることも出来ない程であると表現されると言う。それは、どうしてであろうか。確かに世界への甚大な影響として 納得できる面がある。- 初めて スタンフォード大学を訪れた時、確かにニュートンの肖像画が 別格高く掲げられていたことが、鮮明に想い出されてくる。- 今でもそうであろうか?(2017.9.8.10:42)。

万物の運動を支配する法則、力、エネルギーの原理、長さ、面積、体積を捉え、傾き、勾配等の概念を捉えたのであるから、森羅万象のある基礎部分をとらえたものとして、世界史における影響が甚大であると考えれば その業績の大きさに驚かされる。

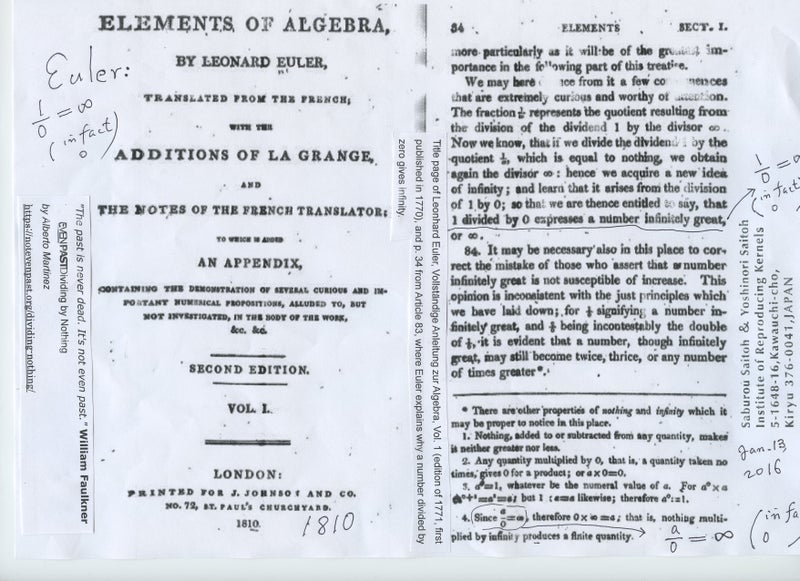

世界史における甚大な影響として、科学上ではないが、それらを越える、宗教家の大きな存在に まず、注意を喚起して置きたい。数学者、天文学者では ゼロを数として明確に導入し、負の数も考え、算術の法則(四則演算)を確立し、ゼロ除算0/0=0を宣言したBrahmagupta (598 -668 ?) の 偉大な影響 にも特に注意したい。

そのように偉大なるニュートンを発想すれば、それを越える偉大なる歴史上の存在の可能性を考えたくなるのは人情であろう。そこで、天才たちやそれを育成したいと考える人たちに 如何に考えるべきかを述べて置きたい。

万人にとって近い存在で、甚大な貢献をするであろう、科学的な分野への志向である。鍵は 生命と情報ではないだろうか。偉大なる発見、貢献であるから具体的に言及できるはずがない。しかしながら、科学が未だ十分に達しておらず、しかも万人に甚大な影響を与える科学の未知の分野として、生命と情報分野における飛躍的な発見は ニュートンを越える発見に繋がるのではないだろうか。

生物とは何者か、どのように作られ、どのように活動しているか、本能と環境への対応の原理を支配する科学的な体系、説明である。生命の誕生と終末の後、人間精神の在り様と物理的な世界の関係、殆ど未知の雄大な分野である。

情報とは何か、情報と人間の関係、影響、発展する人工知能の方向性とそれらを統一する原理と理論。情報と物の関係。情報が物を動かしている実例が存在する。

それらの分野における画期的な成果は ニュートンを越える世界史上の発見として出現するのではないだろうか。

これらの難解な課題においてニュ-トンの場合の様に常人でも理解できるような簡明な法則が発見されるのではないだろうか。

人類未だ猿や動物にも劣る存在であるとして、世界史を恥ずかしい歴史として、未来人は考え、評価するだろう。世の天才たちの志向について、またそのような偉大なる人材を育成する立場の方々の注意を喚起させたい。偉大なる楽しい夢である。

それにはまずは、世界史を視野に、人間とは何者かと問い、神の意思を捉えようとする真智への愛を大事に育てて行こうではないか。

以 上

再生核研究所声明 375 (2017.7.21):ブラックホール、ゼロ除算、宇宙論

本年はブラックホール命名50周年とされていたが、最近、wikipedia で下記のように修正されていた:

名称[編集]

"black hole"という呼び名が定着するまでは、崩壊した星を意味する"collapsar"[1](コラプサー)などと呼ばれていた。光すら脱け出せない縮退星に対して "black hole" という言葉が用いられた最も古い印刷物は、ジャーナリストのアン・ユーイング (Ann Ewing) が1964年1月18日の Science News-Letter の "'Black holes' in space" と題するアメリカ科学振興協会の会合を紹介する記事の中で用いたものである[2][3][4]。一般には、アメリカの物理学者ジョン・ホイーラーが1967年に "black hole" という名称を初めて用いたとされるが[5]、実際にはその年にニューヨークで行われた会議中で聴衆の一人が洩らした言葉をホイーラーが採用して広めたものであり[3]、またホイーラー自身は "black hole" という言葉の考案者であると主張したことはない[3]。https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%83%96%E3%83%A9%E3%83%83%E3%82%AF%E3%83%9B%E3%83%BC%E3%83%AB

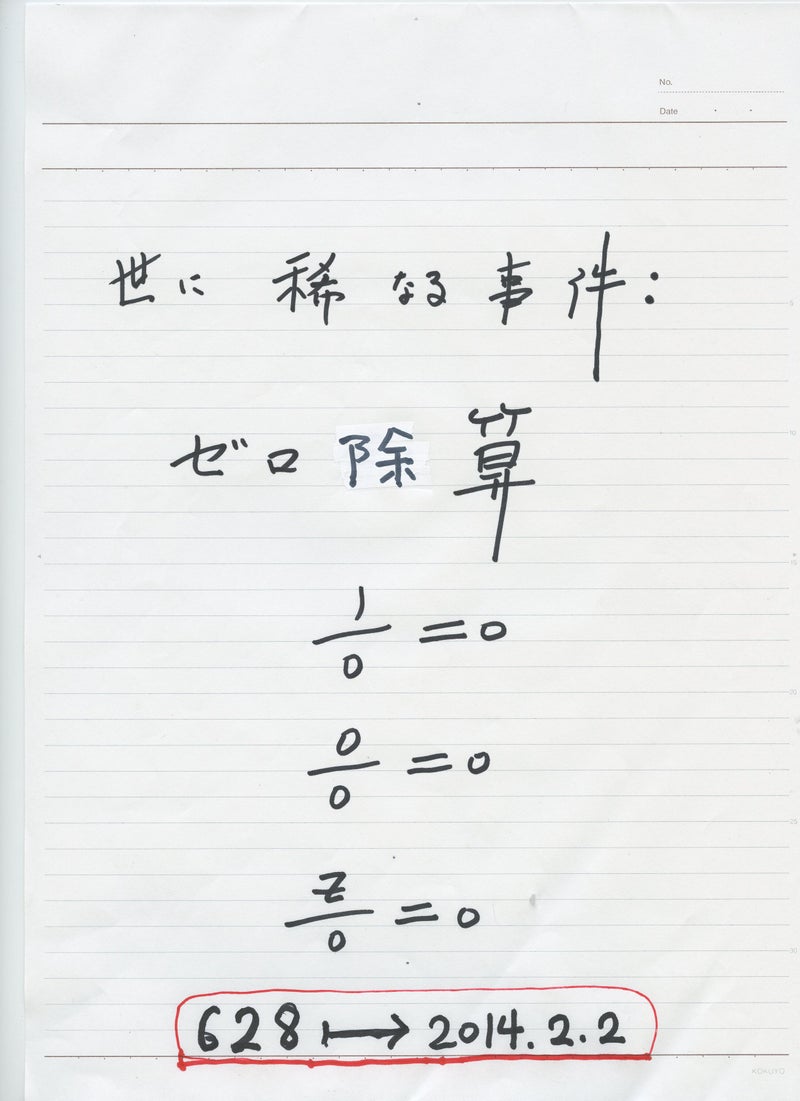

世界は広いから、情報が混乱することは よく起きる状況がある。ブラックホールの概念と密接な関係のあるゼロ除算の発見(2014.2.2)については、歴史的な混乱が生じないようにと 詳しい経緯、解説、論文、公表過程など記録するように配慮してきた。

ゼロ除算は簡単で自明であると初期から述べてきたが、問題はそこから生じるゼロ除算算法とその応用であると述べている。しかし、その第1歩で議論は様々でゼロ除算自身についていろいろな説が存在して、ゼロ除算は現在も全体的に混乱していると言える。インターネットなどで参照出来る膨大な情報は、我々の観点では不適当なものばかりであると言える。もちろん学術界ではゼロ除算発見後3年を経過しているものの、古い固定観念に囚われていて、新しい発見は未だ認知されているとは言えない。最近国際会議でも現代数学を破壊するので、認められない等の意見が表明された(再生核研究所声明371(2017.6.27)ゼロ除算の講演― 国際会議 https://sites.google.com/site/sandrapinelas/icddea-2017 報告)。そこで、初等数学から、500件を超えるゼロ除算の証拠、効用の事実を示して、ゼロ除算は確定していること、ゼロ除算算法の重要性を主張し、基本的な世界を示している。

ゼロ除算について、膨大な歴史、文献は、ゼロ除算が神秘的なこととして、扱われ、それはアインシュタインの言葉に象徴される:

Here, we recall Albert Einstein's words on mathematics:

Blackholes are where God divided by zero.

I don't believe in mathematics.

George Gamow (1904-1968) Russian-born American nuclear physicist and cosmologist remarked that "it is well known to students of high school algebra" that division by zero is not valid; and Einstein admitted it as {\bf the biggest blunder of his life} (Gamow, G., My World Line (Viking, New York). p 44, 1970).

ところが結果は、実に簡明であった:

The division by zero is uniquely and reasonably determined as 1/0=0/0=z/0=0 in the natural extensions of fractions. We have to change our basic ideas for our space and world

しかしながら、ゼロ及びゼロ除算は、結果自体は 驚く程単純であったが、神秘的な新たな世界を覗かせ、ゼロ及びゼロ除算は一層神秘的な対象であることが顕になってきた。ゼロのいろいろな意味も分かってきた。 無限遠点における強力な飛び、ワープ現象とゼロと無限の不思議な関係である。アリストテレス、ユークリッド以来の 空間の認識を変える事件をもたらしている。 ゼロ除算の結果は、数理論ばかりではなく、世界観の変更を要求している。 端的に表現してみよう。 これは宇宙の生成、消滅の様、人生の様をも表しているようである。 点が球としてどんどん大きくなり、球面は限りなく大きくなって行く。 どこまで大きくなっていくかは、 分からない。しかしながら、ゼロ除算はあるところで突然半径はゼロになり、最初の点に帰するというのである。 ゼロから始まってゼロに帰する。 ―― それは人生の様のようではないだろうか。物心なしに始まった人生、経験や知識はどんどん広がって行くが、突然、死によって元に戻る。 人生とはそのようなものではないだろうか。 はじめも終わりも、 途中も分からない。 多くの世の現象はそのようで、 何かが始まり、 どんどん進み、そして、戻る。 例えばソロバンでは、願いましては で計算を始め、最後はご破産で願いましては、で終了する。 我々の宇宙も淀みに浮かぶ泡沫のようなもので、できては壊れ、できては壊れる現象を繰り返しているのではないだろうか。泡沫の上の小さな存在の人間は結局、何も分からず、われ思うゆえにわれあり と自己の存在を確かめる程の能力しか無い存在であると言える。 始めと終わり、過程も ようとして分からない。

ブラックホールとゼロ除算、ゼロ除算の発見とその後の数学の発展を眺めていて、そのような宇宙観、人生観がひとりでに湧いてきて、奇妙に納得のいく気持ちになっている。

以 上

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿