The Universe According To Albert Einstein: Relativity

Bettmann/Bettmann Archive

Albert Einstein would have been 139 years old Wednesday. Happy Birthday!

Einstein's science, and general views on humanity, have profoundly changed the way we see ourselves and the world we live in. He was not faultless, as no human is. He was an absent father and unfaithful husband. He lived in very different times, and — right or wrong from our current standards — we must analyze facts within their cultural context. Einstein epitomizes the intellectual freedom and courageous creativity that, combined with an unbeatable work ethic, defines true genius.

To shake the foundations of knowledge one needs at least two things: to believe deeply in his ideas and to have the courage to go against the established order. In the sciences, to be successful in shaking the foundations of knowledge so as to promote change, one also needs to be right.

When Einstein came into the science scene at the turn of the 20th century, physics was in crisis. The physics developed from Galileo up to 1899 had three pillars: mechanics, electromagnetism and thermodynamics, the study of heat. And the three pillars were on shaky ground, as physicists couldn't use them to explain a series of phenomena that had been recently discovered in the lab and in the skies. New ideas were badly needed, but not much was coming forth. It was the perfect moment for a trailblazer.

First, there was trouble with light and its propagation. After a debate that lasted for centuries, people were convinced that light was a wave. (The other option, defended by Issac Newton, was that light was made of little bulletlike particles.) That being the case, and as with any other wave, light had to propagate in a material medium. Water waves, for example, travel in water; sound waves in air. Light? Well, for us to see light from distant stars, the medium had to be transparent. It also had to be very light so as not to slow down the orbits of planets. Finally, it had to be very rigid, so as to allow for the propagation of very fast waves: It was well-known by then that light traveled at about 186,000 miles per second in empty space.

What kind of medium could this be? Stumped, the greatest physicists of the 19th century came up with a wild idea: Imagine that all of space is filled with an imponderable medium called the ether. What it was, no one knew. Its sole purpose was to allow light to propagate. With hindsight, we could call it magical stuff. Even as attempts to find it failed, physicists would not let go. The alternative, having light propagating in empty space, sounded even crazier.

Enter Einstein. In 1905, he proposes his special theory of relativity, whereby he singlehandedly destroyed the notions of absolute space and time, and the need for an ether. According to the theory, now one of the greatest success stories in the history of thought, the notions of space as a rigid stage at which things just happen and of time as a steadily flowing river, are just an illusion caused by our myopic view of reality. And it's all light's fault.

Space would only be a rigid stage and time would only be a steady river if light could travel from Point A to Point B instantaneously. (That is if light traveled with an infinite speed.) But it doesn't. Our illusion is corrected once we incorporate the fact that light has a finite speed of propagation, even if it's so ridiculously high. (In fact, it is its enormous value that makes our illusions so persistent and convincing.) Once the correction is factored into our studies of motion, everything changes. An observer at rest that measures the length of a moving bus will obtain a different result from the passengers in the bus. To her, the moving bus will be shorter. If she also saw a clock attached to the bus, she would notice that the seconds pass slower for it than for the watch on her wrist. Amazed, she would conclude that moving objects shorten in the direction of their motion and that moving clocks tick slower.

The effects, called length contraction and time dilation, become more pronounced as the speed of the moving object approaches the speed of light. Remarkably, Einstein also showed, in a second paper he wrote that same year, that no object with mass could ever reach the speed of light. Mass itself grows with speed and becomes infinitely large at the speed of light. Only light itself, or another entity with no mass, could travel at light speed. And by the way, all this is perfectly consistent with light traveling in empty space. No ether. Light is like nothing else in the cosmos.

In 1915, Einstein expanded his theory to include motions with variable speeds (i.e., with acceleration). His theory of general relativity, arguably one of the towering achievements of the human intellect, imprinted the plasticity of space and time into the fabric of the universe itself. Now, the presence of any material object (or merely energy) could bend space and alter the flow of time. Space and time became literally pliable. For example, a light ray from a distant star would be deviated from a straight line as it passed by the sun. (It does as it passes by you, too, but the bending is so small as to be literally immeasurable.) In 1919, two expeditions were sent to test Einstein's prediction of this phenomenon. Their data, despite bad weather and measurement issues, were conclusive: Einstein was right.

Later on, Einstein's prediction for the flow of time was also confirmed: Time slows down in strong gravity. A clock on the top of the Empire State Building ticks faster than one on the ground. But the effect is tiny: If you were to spend your lifetime on top of the Empire State Building you would lose 104 millionths of a second. Even more fun: In a 79-year lifetime, the cells in your brain age faster than those in your feet by about 45 billionths of a second.

Einstein was the first to apply his ideas of space and time plasticity to the universe as a whole. In 1919, he devised a model for the entire universe: a static, spherical, perfectly symmetric cosmos, with matter homogeneously distributed everywhere, reflecting a mix of Platonic perfection and of Ockham's Razor. That first model, even if wrong, became the inspiration for all the work on modern cosmology that followed it, including the now widely-accepted Big Bang model, whereby the universe emerged from an event 13.8 billion years ago and has been expanding and cooling ever since. Black holes, gravitational waves, all of this follows from Einstein's general theory. Oh yes, and so does the accuracy of your GPS, which needs elements from both the special and the general theories.

Remarkably, all this relativity stuff was only one of Einstein's playgrounds. The other, his muse and demon, was quantum theory. Next week, I'll take it up from here, and explain why Einstein got his Nobel prize for his ideas on the nature of light (being both a wave and a particle) and not for relativity. And why he was haunted by the quantum ghost to the end of his life.

Note: As this article was being edited, we learned of Stephen Hawking's passing. An uncanny coincidence, he was fond of telling that he was born on the 300th anniversary of Galileo's death; and now, he passes away on the 139th anniversary of Einstein's birth.

Stephen Hawking was one of those rare life heroes who shone above all of us as a beacon. Not just as a brilliant physicist whose contributions to our understanding of the universe and of black holes will remain forever in the annals of science, but also as a life-loving, amazingly resilient person. He had the generosity of heart to share his knowledge and inspire millions of readers around the globe. His love for life must be celebrated and remembered by all of us, scientists or not.

Marcelo Gleiser is a theoretical physicist and writer — and a professor of natural philosophy, physics and astronomy at Dartmouth College. He is the director of the Institute for Cross-Disciplinary Engagement at Dartmouth, co-founder of 13.7 and an active promoter of science to the general public. His latest book is The Simple Beauty of the Unexpected: A Natural Philosopher's Quest for Trout and the Meaning of Everything. You can keep up with Marcelo on Facebook and Twitter: @mgleiser

とても興味深く読みました:ゼロ除算発見4周年を超えました:

再生核研究所声明 411(2018.02.02): ゼロ除算発見4周年を迎えて

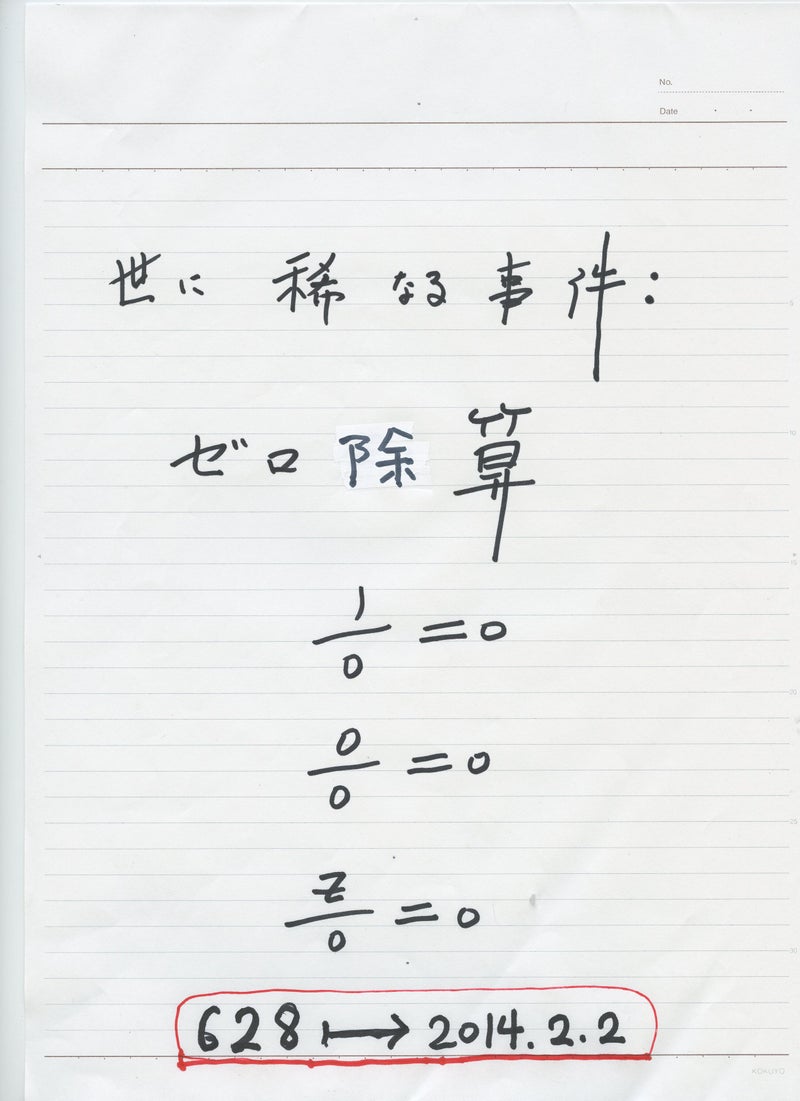

ゼロ除算100/0=0を発見して、4周年を迎える。 相当夢中でひたすらに その真相を求めてきたが、一応の全貌が見渡せ、その基礎と展開、相当先も展望できる状況になった。論文や日本数学会、全体講演者として招待された大きな国際会議などでも発表、著書原案154ページも纏め(http://okmr.yamatoblog.net/)基礎はしっかりと確立していると考える。数学の基礎はすっかり当たり前で、具体例は700件を超え、初等数学全般への影響は思いもよらない程に甚大であると考える: 空間、初等幾何学は ユークリッド以来の基本的な変更で、無限の彼方や無限が絡む数学は全般的な修正が求められる。何とユークリッドの平行線の公理は成り立たず、すべての直線は原点を通るというが我々の数学、世界であった。y軸の勾配はゼロであり、\tan(\pi/2) =0 である。 初等数学全般の修正が求められている。

数学は、人間を超えたしっかりとした論理で組み立てられており、数学が確立しているのに今でもおかしな議論が世に横行し、世の常識が間違っているにも拘わらず、論文発表や研究がおかしな方向で行われているのは 誠に奇妙な現象であると言える。ゼロ除算から見ると数学は相当おかしく、年々間違った数学やおかしな数学が教育されている現状を思うと、研究者として良心の呵責さえ覚える。

複素解析学では、無限遠点はゼロで表されること、円の中心の鏡像は無限遠点では なくて中心自身であること、ローラン展開は孤立特異点で意味のある、有限確定値を取ることなど、基本的な間違いが存在する。微分方程式などは欠陥だらけで、誠に恥ずかしい教科書であふれていると言える。 超古典的な高木貞治氏の解析概論にも確かな欠陥が出てきた。勾配や曲率、ローラン展開、コーシーの平均値定理さえ進化できる。

ゼロ除算の歴史は、数学界の避けられない世界史上の汚点に成るばかりか、人類の愚かさの典型的な事実として、世界史上に記録されるだろう。この自覚によって、人類は大きく進化できるのではないだろうか。

そこで、我々は、これらの認知、真相の究明によって、数学界の汚点を解消、世界の文化への貢献を期待したい。

ゼロ除算の真相を明らかにして、基礎数学全般の修正を行い、ここから、人類への教育を進め、世界に貢献することを願っている。

ゼロ除算の発展には 世界史がかかっており、数学界の、社会への対応をも 世界史は見ていると感じられる。 恥の上塗りは世に多いが、数学界がそのような汚点を繰り返さないように願っている。

人の生きるは、真智への愛にある、すなわち、事実を知りたい、本当のことを知りたい、高級に言えば神の意志を知りたいということである。そこで、我々のゼロ除算についての考えは真実か否か、広く内外の関係者に意見を求めている。関係情報はどんどん公開している。

4周年、思えば、世の理解の遅れも反映して、大丈夫か、大丈夫かと自らに問い、ゼロ除算の発展よりも基礎に、基礎にと向かい、基礎固めに集中してきたと言える。それで、著書原案ができたことは、楽しく充実した時代であったと喜びに満ちて回想される。

以 上

List of division by zero:

\bibitem{os18}

H. Okumura and S. Saitoh,

Remarks for The Twin Circles of Archimedes in a Skewed Arbelos by H. Okumura and M. Watanabe, Forum Geometricorum.

Saburou Saitoh, Mysterious Properties of the Point at Infinity、

arXiv:1712.09467 [math.GM]

arXiv:1712.09467 [math.GM]

Hiroshi Okumura and Saburou Saitoh

The Descartes circles theorem and division by zero calculus. 2017.11.14

L. P. Castro and S. Saitoh, Fractional functions and their representations, Complex Anal. Oper. Theory {\bf7} (2013), no. 4, 1049-1063.

M. Kuroda, H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh, and M. Yamane,

New meanings of the division by zero and interpretations on $100/0=0$ and on $0/0=0$, Int. J. Appl. Math. {\bf 27} (2014), no 2, pp. 191-198, DOI: 10.12732/ijam.v27i2.9.

T. Matsuura and S. Saitoh,

Matrices and division by zero z/0=0,

Advances in Linear Algebra \& Matrix Theory, 2016, 6, 51-58

Published Online June 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/alamt

\\ http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/alamt.2016.62007.

T. Matsuura and S. Saitoh,

Division by zero calculus and singular integrals. (Submitted for publication).

T. Matsuura, H. Michiwaki and S. Saitoh,

$\log 0= \log \infty =0$ and applications. (Differential and Difference Equations with Applications. Springer Proceedings in Mathematics \& Statistics.)

H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh and M.Yamada,

Reality of the division by zero $z/0=0$. IJAPM International J. of Applied Physics and Math. 6(2015), 1--8. http://www.ijapm.org/show-63-504-1.html

H. Michiwaki, H. Okumura and S. Saitoh,

Division by Zero $z/0 = 0$ in Euclidean Spaces,

International Journal of Mathematics and Computation, 28(2017); Issue 1, 2017), 1-16.

H. Okumura, S. Saitoh and T. Matsuura, Relations of $0$ and $\infty$,

Journal of Technology and Social Science (JTSS), 1(2017), 70-77.

S. Pinelas and S. Saitoh,

Division by zero calculus and differential equations. (Differential and Difference Equations with Applications. Springer Proceedings in Mathematics \& Statistics).

S. Saitoh, Generalized inversions of Hadamard and tensor products for matrices, Advances in Linear Algebra \& Matrix Theory. {\bf 4} (2014), no. 2, 87--95. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ALAMT/

S. Saitoh, A reproducing kernel theory with some general applications,

Qian,T./Rodino,L.(eds.): Mathematical Analysis, Probability and Applications - Plenary Lectures: Isaac 2015, Macau, China, Springer Proceedings in Mathematics and Statistics, {\bf 177}(2016), 151-182. (Springer) .

再生核研究所声明 420(2018.3.2): ゼロ除算は正しいですか,合っていますか、信用できますか - 回答

ゼロ除算に 興味を抱いている方の 率直な 疑念です。大きな国際会議で、感情的になって 現代の数学を破壊するもので 全く認められないと発言された方がいる。現代初等数学には基本的な欠陥があって、我々の空間の認識は ユークリッド以来の修正が求められ、初等数学全般の再構成が要求されていると述べている。それで、もちろん、慎重に 慎重に対応しているのは当然である。

本来 数学者は 論理に厳格で 数学の世界ほど 間違えの無い世界は無いと言えるのではないだろうか。 実際、一人前の数学者とは、独自の価値観を有し、論理的な間違いはしない者である と考えられているのではないだろうか。2000年を越える超古典的な数学に反した 新しい世界が現れたので、異常に慎重になり、大丈夫か大丈夫かと4年間を越えて反芻して来た(再生核研究所声明 411(2018.02.02): ゼロ除算発見4周年を迎えて)。 そこで、ゼロ除算の成果における信頼性を客観的に 疑念に対する回答として纏めて置こう。これらは、貴重な記録になると考えられる。

まず、研究成果は 3年半を越えて、広く公開している:

数学基礎学力研究会 サイトで解説が続けられている:http://www.mirun.sctv.jp/~suugaku/

また、ohttp://okmr.yamatoblog.net/ に 関連情報を公開している。

ゼロ除算の研究は、内外の研究者に意見を求められながら共同で進め、12編を越える論文を出版確定にしている。日本数学会では6期3年間を越えて関係講演を行い、成果を発表して来た。 またその際、ゼロ除算の解説冊子(2015.1.14付け)を1000部以上広く配布して意見を求めてきたが、論理的な不備などはどこからも指摘されていない。ここ4年間海外の関係専門家と250以上のメールで議論してきた(ある人がそう述べてきた:2018年2月27日 18:45 Since then I have received about 250 messages from you about it. Unbelievable! :2018年2月27日 18:45)が 論理的な不備は指摘されなく、関係者の諒解(理解)が付いていると判断されている。逆に他の理論については 全て具体的に批判し、良くないと述べている。50カ国200名以上参加の大きな国際会議に 全体講演者として招待され、講演を行い、かつ論文がその会議禄に2編Springer社から出版される。公開していたゼロ除算の総合的な研究著書原案154ページに対して、イギリスの出版社が出版を勧め、外部審査、社内審査を終えて、著書の出版を決定している。

ゼロ除算を裏付ける知見は 初等数学全般から700件を超え、公開している。共著者として論文執筆に参加している人は、代表者以外内外8名である。

以上の状況は ゼロ除算の数学的な信用性を裏付けていると考えるが、如何であろうか。

以 上

再生核研究所声明 414(2018.2.14): 第1回ゼロ除算研究集会基調講演要旨

(日時:2018.3.15(木曜日) 11:00 - 15:00 場所: 群馬大学大学院 理工学府)

ゼロで割る問題 例えば100/0の意味、 ゼロ除算は インドで628年ゼロの発見以来の問題として、神秘的な歴史を辿って来ていて、最近でも大論文がおかしな感じで発表されている。ゼロ除算は 物理的には アリストテレスが 最初に不可能であると専門家が論じていて、それ以来物理学上での問題意識は強く、アインシュタインの人生最大の関心事であったという。ゼロ除算は数学的には 不可能であるとされ、数学的ではなく、物理学上の問題とゼロ除算が計算機障害を起こすことから、論理的な回避を目指して、今なお研究が盛んに進められている。

しかるに、我々は約4年前に全く、自然で簡単な 数学的に完全である と考えるゼロ除算を発見して現在、全体の様子が明かに成って来た。そこで、ゼロ除算を歴史的に振り返り、我々の発見した新しい数学を紹介したい。

まず、歴史、結果と、結果の意義と意味、を簡潔に 誰にでも分かるように解説したい。

簡単な結果が、アリストテレス、ユークリッド以来の 我々の空間の認識を変える、実は新しい世界を拓いていること。それらを実証するための 具体例を沢山挙げる。我々の空間の認識は 2000年以上 適切ではなく、したがって 初等数学全般に欠陥があることを 沢山の具体例で示す。

ゼロ除算は新しい世界を拓いており、この分野の研究を進め、世界史に貢献する意志を持ちたい。

尚、ゼロおよび算術の確立者 Brahmagupta (598 -668 ?) は1300年以上も前に、0/0=0 と定義していたのに、世界史は それは間違いであるとしてきた、数学界と世界史の恥を反省して、世界史の進化を図りたい。

以 上

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿