La longue histoire du zéro, ce « rien » si important

Author

Disclosure statement

Ittay Weiss does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Partners

University of Portsmouth provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

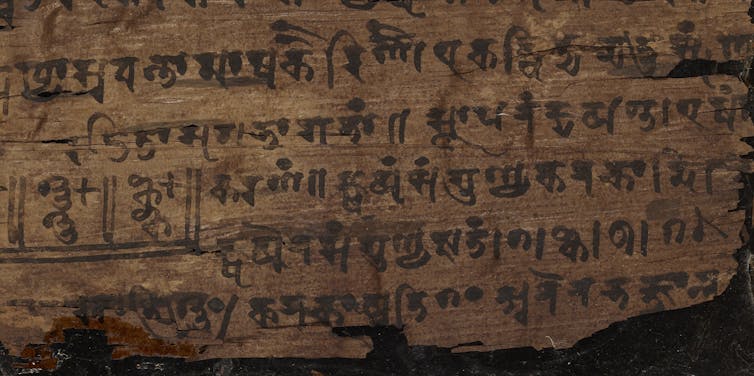

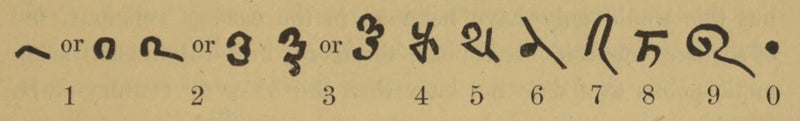

Un petit point gravé dans un morceau d’écorce de boulot marque l’un des événements les plus importants de l’histoire des mathématiques. L’écorce est en réalité un fragment d’un document connu sous le nom de manuscrit de Bakshali. Ce point est la première utilisation connue du nombre zéro. Des chercheurs de l’université d’Oxford ont récemment découvertque ce document est de 500 ans plus anciens par rapport aux dernières estimations, ils l’ont daté du troisième ou quatrième siècle après J.C. Une découverte majeure !

Il est aujourd’hui bien difficile d’imaginer comment faire des maths sans utiliser le zéro. Dans un système numérique, tel que le système décimal que nous utilisons, la position d’un chiffre est vraiment importante. Par exemple, la réelle différence entre 100 et 1 000 000 est la position du 1, le symbole 0 servant de ponctuation.

Cela dit, pendant des milliers d’années on s’en est bien passé. Les Sumériens, 5 000 ans avant notre ère, utilisaient un système « positionnel » mais sans 0. Dans des formes rudimentaires, un symbole ou un espace était utilisé pour distinguer, par exemple, 204 et 20000004. Ce symbole n’était néanmoins jamais utilisé à la fin d’un nombre, la différence entre 5 et 500 devait alors être déterminée par le contexte.

Une brève histoire du zéro

L’arrivée tardive du zéro est due, en partie, à une appréciation négative du concept de néant dans certaines cultures. La philosophie occidentale est remplie d’idées fausses à propos du néant. Parmenides, penseur grec du Ve siècle avant J.C., proclama par exemple que le néant ne pouvait exister, parce que parler de quelque chose le fait, de facto, exister.

Après l’avènement de la chrétienté, les dirigeants religieux européens expliquèrent que puisque Dieu est dans tout ce qui existe, alors toute représentation du néant devait être satanique. Dans l’espoir de sauver l’humanité du diable, ils bannirent rapidement le zéro de la société alors que dans le même temps, les marchands continuaient à l’utiliser en secret !

Dans la philosophie bouddhiste, au contraire, le concept de néant n’est pas seulement dénué de tout parfum démoniaque mais est une idée centrale dans les tentatives des adeptes pour atteindre le nirvana. Un tel état d’esprit, permet une représentation mathématique du zéro. En fait, le mot anglais zero est dérivé à l’origine du mot hindi « sunyata », signifiant « néant » et est un concept central dans le bouddhisme. Pour arriver au terme français, sunyata est passé par l’arabe cifron puis l’italien zefiro.

Après que le zéro a émergé dans l’Inde ancienne, il lui a fallu près de mille ans pour s’enraciner en Europe, bien après la Chine et le Moyen-Orient. En 1200, le mathématicien italien Fibonacci, qui amena le système décimal en Europe écrivait :

La méthode des Indiens surpasse toute méthode connue pour calculer. C’est une méthode fantastique. Ils font leurs calculs en utilisant neuf chiffres et le symbole zéro.

Cette méthode supérieure de calcul, clairement semblable à la notre, libéra les mathématiciens des opérations simples mais ennuyeuses, leur permit de s’attaquer à des problèmes bien plus complexes et d’étudier les propriétés générales des nombres. Par exemple, cela a permis le travail du mathématicien et astronome indien Brahmagupta, considéré comme le père de l’algèbre moderne.

Algorithmes et calculs

La méthode indienne est puissante car elle permet de générer des règles simples de calcul. Imaginez-vous en train d’essayer d’expliquer comment faire une longue addition sans utiliser un symbole pour le zéro. Pour chaque règle que vous pourriez inventer, il y aurait bien trop d’exceptions. Le mathématicien perse du neuvième siècle Al-Khwarizmi a été le premier à méticuleusement noter et exploiter ces instructions arithmétiques, ce qui allait rendre, au final, les abaques obsolètes.

De telles instructions mécaniques illustrèrent qu’une partie des mathématiques était automatisable et cela allait mener au développement des ordinateurs modernes. Le mot « algorithme » utilisé pour décrire un ensemble d’instructions basiques est d’ailleurs dérivé du nom Al Khwarizmi.

L’invention du zéro a également créé une nouvelle manière plus précise de décrire les fractions. Ajouter des zéros à la fin d’un nombre augmente sa grandeur ; ajouter des zéros au début de ce nombre, après la virgule, la diminue. Placer infiniment des nombres à droite de la virgule correspond à une précision infinie. Une telle précision était exactement ce que les grands penseurs du XVIIe siècle Isaac Newton et Gottfried Leibniz avaient besoin pour développer leurs travaux sur le calcul infinitésimal.

Ainsi l’algèbre, les algorithmes, le calcul infinitésimal, trois piliers des mathématiques modernes sont le résultat de la notation du néant. Les maths sont une science des entités invisibles que nous ne pouvons comprendre seulement une fois écrites. L’Inde, en ajoutant le zéro au système des nombres, libéra le vrai pouvoir des nombres, faisant passer les maths de l’enfance à l’adolescence et du rudimentaire vers sa sophistication actuelle !https://theconversation.com/la-longue-histoire-du-zero-ce-rien-si-important-84739

とても興味深く読みました:

\documentclass[12pt]{article}

\usepackage{latexsym,amsmath,amssymb,amsfonts,amstext,amsthm}

\numberwithin{equation}{section}

\begin{document}

\title{\bf Announcement 380: What is the zero?\\

(2017.8.21)}

\author{{\it Institute of Reproducing Kernels}\\

Kawauchi-cho, 5-1648-16,\\

Kiryu 376-0041, Japan\\

}

\date{\today}

\maketitle

\section{What is the zero?}

The zero $0$ as the complex number or real number is given clearly by the axions by the complex number field and real number field.

For this fundamental idea, we should consider the {\bf Yamada field} containing the division by zero. The Yamada field and the division by zero calculus will arrange our mathematics, beautifully and completely; this will be our natural and complete mathematics.

\medskip

\section{ Double natures of the zero $z=0$}

The zero point $z=0$ represents the double natures; one is the origin at the starting point and another one is a representation of the point at infinity. One typical and simple example is given by $e^0 = 1,0$, two values. {\bf God loves two}.

\section{Standard value}

\medskip

The zero is a center and stand point (or bases, a standard value) of the coordinates - here we will consider our situation on the complex or real 2 dimensional spaces. By stereographic

projection mapping or the Yamada field, the point at infinity $1/0$ is represented by zero. The origin of the coordinates and the point at infinity correspond each other.

As the standard value, for the point $\omega_n = \exp \left(\frac{\pi}{n}i\right)$ on the unit circle $|z|=1$ on the complex $z$-plane is, for $n = 0$:

\begin{equation}

\omega_0 = \exp \left(\frac{\pi}{0}i\right)=1, \quad \frac{\pi}{0} =0.

\end{equation}

For the mean value

$$

M_n = \frac{x_1 + x_2 +... + x_n}{n},

$$

we have

$$

M_0 = 0 = \frac{0}{0}.

$$

\medskip

\section{ Fruitful world}

\medskip

For example, for very and very general partial differential equations, if the coefficients or terms are zero, then we have some simple differential equations and the extreme case is all the terms are zero; that is, we have trivial equations $0=0$; then its solution is zero. When we consider the converse, we see that the zero world is a fruitful one and it means some vanishing world. Recall Yamane phenomena (\cite{kmsy}), the vanishing result is very simple zero, however, it is the result from some fruitful world. Sometimes, zero means void or nothing world, however, it will show {\bf some changes} as in the Yamane phenomena.

\section{From $0$ to $0$; $0$ means all and all are $0$}

\medskip

As we see from our life figure (\cite{osm}), a story starts from the zero and ends with the zero. This will mean that $0$ means all and all are $0$. The zero is a {\bf mother} or an {\bf origin} of all.

\medskip

\section{ Impossibility}

\medskip

As the solution of the simplest equation

\begin{equation}

ax =b

\end{equation}

we have $x=0$ for $a=0, b\ne 0$ as the standard value, or the Moore-Penrose generalized inverse. This will mean in a sense, the solution does not exist; to solve the equation (6.1) is impossible.

We saw for different parallel lines or different parallel planes, their common points are the origin. Certainly they have the common points of the point at infinity and the point at infinity is represented by zero. However, we can understand also that they have no solutions, no common points, because the point at infinity is an ideal point.

Of course. we can consider the equation (6.1) even the case $a=b=0$ and then we have the solution $x=0$ as we stated.

We will consider the simple differential equation

\begin{equation}

m\frac{d^2x}{dt^2} =0, m\frac{d^2y}{dt^2} =-mg

\end{equation}

with the initial conditions, at $t =0$

\begin{equation}

\frac{dx}{dt} = v_0 \cos \alpha , \frac{d^2x}{dt^2} = \frac{d^2y}{dt^2}=0.

\end{equation}

Then, the highest high $h$, arriving time $t$, the distance $d$ from the starting point at the origin to the point $y(2t) =0$ are given by

\begin{equation}

h = \frac{v_0 \sin^2 \alpha}{2g}, d= \frac{v_0\sin \alpha}{g}

\end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}

t= \frac{v_0 \sin \alpha}{g}.

\end{equation}

For the case $g=0$, we have $h=d =t=0$. We considered the case that they are the infinity; however, our mathematics means zero, which shows impossibility.

These phenomena were looked many cases on the universe; it seems that {\bf God does not like the infinity}.

\bibliographystyle{plain}

\begin{thebibliography}{10}

\bibitem{kmsy}

M. Kuroda, H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh, and M. Yamane,

New meanings of the division by zero and interpretations on $100/0=0$ and on $0/0=0$,

Int. J. Appl. Math. {\bf 27} (2014), no 2, pp. 191-198, DOI: 10.12732/ijam.v27i2.9.

\bibitem{msy}

H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh, and M.Yamada,

Reality of the division by zero $z/0=0$. IJAPM International J. of Applied Physics and Math. {\bf 6}(2015), 1--8. http://www.ijapm.org/show-63-504-1.html

\bibitem{ms}

T. Matsuura and S. Saitoh,

Matrices and division by zero $z/0=0$, Advances in Linear Algebra

\& Matrix Theory, 6 (2016), 51-58. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/alamt.2016.62007 http://www.scirp.org/journal/alamt

\bibitem{mos}

H. Michiwaki, H. Okumura, and S. Saitoh,

Division by Zero $z/0 = 0$ in Euclidean Spaces.

International Journal of Mathematics and Computation Vol. 28(2017); Issue 1, 2017), 1-16.

\bibitem{osm}

H. Okumura, S. Saitoh and T. Matsuura, Relations of $0$ and $\infty$,

Journal of Technology and Social Science (JTSS), 1(2017), 70-77.

\bibitem{romig}

H. G. Romig, Discussions: Early History of Division by Zero,

American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 31, No. 8. (Oct., 1924), pp. 387-389.

\bibitem{s}

S. Saitoh, Generalized inversions of Hadamard and tensor products for matrices, Advances in Linear Algebra \& Matrix Theory. {\bf 4} (2014), no. 2, 87--95. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ALAMT/

\bibitem{s16}

S. Saitoh, A reproducing kernel theory with some general applications,

Qian,T./Rodino,L.(eds.): Mathematical Analysis, Probability and Applications - Plenary Lectures: Isaac 2015, Macau, China, Springer Proceedings in Mathematics and Statistics, {\bf 177}(2016), 151-182 (Springer).

\bibitem{ttk}

S.-E. Takahasi, M. Tsukada and Y. Kobayashi, Classification of continuous fractional binary operations on the real and complex fields, Tokyo Journal of Mathematics, {\bf 38}(2015), no. 2, 369-380.

\bibitem{ann179}

Announcement 179 (2014.8.30): Division by zero is clear as z/0=0 and it is fundamental in mathematics.

\bibitem{ann185}

Announcement 185 (2014.10.22): The importance of the division by zero $z/0=0$.

\bibitem{ann237}

Announcement 237 (2015.6.18): A reality of the division by zero $z/0=0$ by geometrical optics.

\bibitem{ann246}

Announcement 246 (2015.9.17): An interpretation of the division by zero $1/0=0$ by the gradients of lines.

\bibitem{ann247}

Announcement 247 (2015.9.22): The gradient of y-axis is zero and $\tan (\pi/2) =0$ by the division by zero $1/0=0$.

\bibitem{ann250}

Announcement 250 (2015.10.20): What are numbers? - the Yamada field containing the division by zero $z/0=0$.

\bibitem{ann252}

Announcement 252 (2015.11.1): Circles and

curvature - an interpretation by Mr.

Hiroshi Michiwaki of the division by

zero $r/0 = 0$.

\bibitem{ann281}

Announcement 281 (2016.2.1): The importance of the division by zero $z/0=0$.

\bibitem{ann282}

Announcement 282 (2016.2.2): The Division by Zero $z/0=0$ on the Second Birthday.

\bibitem{ann293}

Announcement 293 (2016.3.27): Parallel lines on the Euclidean plane from the viewpoint of division by zero 1/0=0.

\bibitem{ann300}

Announcement 300 (2016.05.22): New challenges on the division by zero z/0=0.

\bibitem{ann326}

Announcement 326 (2016.10.17): The division by zero z/0=0 - its impact to human beings through education and research.

\bibitem{ann352}

Announcement 352(2017.2.2): On the third birthday of the division by zero z/0=0.

\bibitem{ann354}

Announcement 354(2017.2.8): What are $n = 2,1,0$ regular polygons inscribed in a disc? -- relations of $0$ and infinity.

\bibitem{362}

Announcement 362(2017.5.5): Discovery of the division by zero as

$0/0=1/0=z/0=0$.

\end{thebibliography}

\end{document}

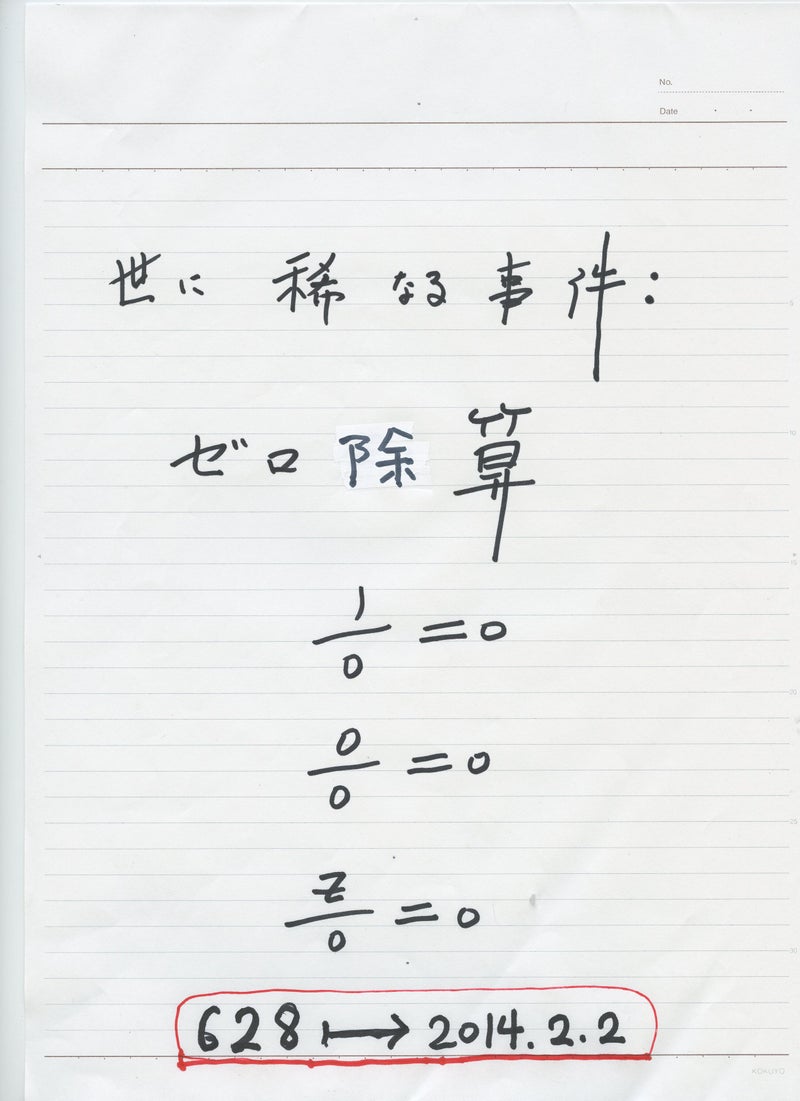

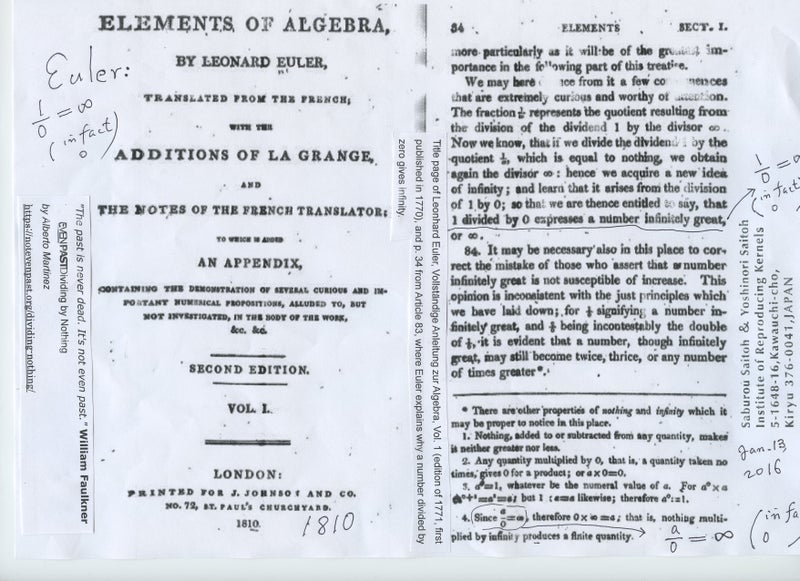

The division by zero is uniquely and reasonably determined as 1/0=0/0=z/0=0 in the natural extensions of fractions. We have to change our basic ideas for our space and world

Division by Zero z/0 = 0 in Euclidean Spaces

Hiroshi Michiwaki, Hiroshi Okumura and Saburou Saitoh

International Journal of Mathematics and Computation Vol. 28(2017); Issue 1, 2017), 1

-16.

http://www.scirp.org/journal/alamt http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/alamt.2016.62007

http://www.ijapm.org/show-63-504-1.html

http://www.diogenes.bg/ijam/contents/2014-27-2/9/9.pdf

http://okmr.yamatoblog.net/division%20by%20zero/announcement%20326-%20the%20divi

http://okmr.yamatoblog.net/

Relations of 0 and infinity

Hiroshi Okumura, Saburou Saitoh and Tsutomu Matsuura:

http://www.e-jikei.org/…/Camera%20ready%20manuscript_JTSS_A…

https://sites.google.com/site/sandrapinelas/icddea-2017

2017.8.21.06:37

再生核研究所声明371(2017.6.27)ゼロ除算の講演― 国際会議 https://sites.google.com/site/sandrapinelas/icddea-2017 報告

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿