Los excéntricos hábitos de Albert Einstein y qué lecciones útiles nos enseñan

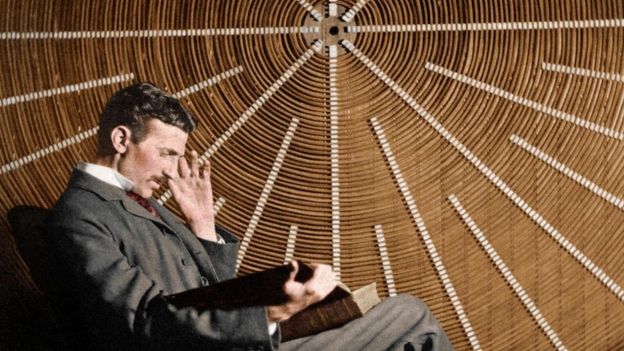

Según el autor Marc J. Seifer, el célebre inventor y físico Nikola Tesla flexionaba los dedos de sus pies todas las noches para estimular sus células cerebrales.

Isaac Newton, mientras tanto, alardeaba sobre los beneficios del celibato, algo que también practicó Tesla aunque, posteriormente, llegó a decir que se había enamorado de una paloma.

Desde Pitágoras y su prohibición de comer frijoles hasta Benjamín Franklin y sus "baños de aire" sin ropa, el camino hacia la grandeza está repleto de hábitos verdaderamente peculiares.

¿Pero si no se tratara de simples datos superficiales?

- ¿Existen realmente las personas sabias? ¿Eres tú una de ellas?

- ¿Cómo saber si eres un genio aunque siempre hayas sacado malas notas?

Según las últimas evidencias, cerca del 40% de lo que diferencia a los "cerebritos" del resto de mortales en la adultez tiene su origen en factores ambientales.

Nos guste o no, nuestros hábitos diarios tienen un poderoso impacto sobre nuestros cerebros, dando forma a su estructura y modificando nuestra forma de pensar.

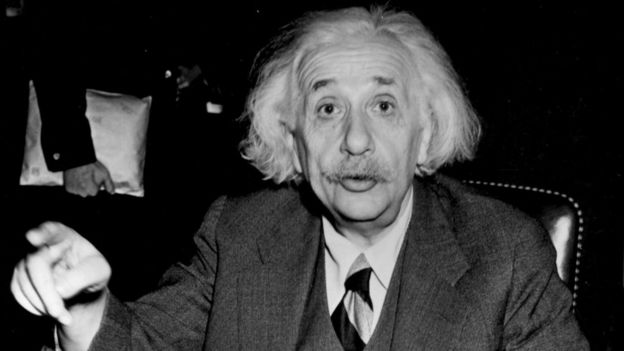

Y entre todas las grandes mentes de la historia, probablemente el maestro de combinar la genialidad con hábitos raros fue Albert Einstein.

¿Quién mejor para buscar pistas de comportamientos que mejoren la mente?

- La nevera de Albert Einstein y la época menos conocida del científico más famoso

- Los ojos de Einstein y el pene de Napoleón: algunas de las reliquias más extrañas de la historia

Dormir 10 horas y siestas de un segundo

Se sabe que dormir es bueno para el cerebro, pero Einstein se tomó ese consejo más en serio que la mayoría.

Derechos de autor de la imagenSCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Derechos de autor de la imagenSCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Supuestamente dormía al menos 10 horas al día (el estadounidense promedio duerme hoy en día 6,8).

Muchas de los avances más radicales en la historia de la humanidad, incluyendo la tabla periódica y la estructura del ADN, supuestamente surgieron mientras sus descubridores estaban inconscientes.

También la teoría de la relatividad de Einstein, que se le ocurrió cuando soñaba con vacas electrocutadas.

¿Pero es esa inspiración del sueño cierta?

Cuando caemos dormidos, el cerebro entra en una serie de ciclos.

Cada 90-120 minutos fluctúa entre el sueño ligero, sueño profundo y la fase REM (movimiento ocular rápido) que, hasta hace poco, se creía desempeñaba el rol principal en el aprendizaje y la memoria.

Pero esa no es toda la historia.

"Pasamos el 60% de nuestra noche en un sueño no REM", enfatiza Stuart Fogel, neurocientífico de la Universidad de Ottawa, Canadá.

Ese tipo de sueño se caracteriza por rápidas ráfagas de actividad cerebral. Ocurren miles de veces en la noche y cada una dura solo unos pocos segundos.

Conocidas como huso del sueño o ritmo sigma, comienzan con un aumento de energía eléctrica generado por las estructuras profundas del cerebro.

Derechos de autor de la imagenSCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Derechos de autor de la imagenSCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

El principal responsable es el tálamo, una región que actúa como el principal "centro de comunicaciones" del cerebro.

Curiosamente, quienes tienen más incidencias de husos del sueño tienden a tener una mayor "inteligencia fluida", la habilidad para resolver nuevos problemas, usar la lógica en nuevas situaciones, e identificar patrones.

Es la clase de inteligencia que Einstein tenía en abundancia y guarda consonancia con su menosprecio por la educación formal y su recomendación de "nunca memorizar algo que puedas consultar".

Aun no se sabe por qué esas ondas serían beneficiosas, pero Fogel cree que podría tener que ver con las regiones activadas en el cerebro (el tálamo y la corteza cerebral).

Afortunadamente para Einstein, también tomaba siestas regularmente.

Según una leyenda apócrifa, para asegurarse de no excederse solía reclinarse en su sillón con una cuchara en la mano y un plato de metal directamente debajo.

Se permitía entonces caer dormido por un segundo, despertándose con el sonido que hacía la cuchara al caerse.

Caminatas diarias

Para Einstein su caminata diaria era algo sagrado.

Al ir y volver a la Universidad de Princeton, EE.UU., recorría en total unos 5km.

Hay muchas evidencias de que caminar mejora la memoria, la creatividad y la solución de problemas.

Derechos de autor de la imagenGETTY IMAGES

Derechos de autor de la imagenGETTY IMAGES

Si lo piensas, no tiene mucho sentido. Es algo que distrae el cerebro de tareas más intelectuales y te fuerza a concentrarte en poner un pie delante del otro y no caerte.

Pero es ahí donde aparece la "hipofrontalidad transitoria" que, básicamente, significa moderar la actividad en ciertas partes del cerebro, especialmente los lóbulos frontales que participan en procesos más elevados como la memoria, el juicio y el lenguaje.

Al reducir un poco esa actividad, el cerebro adopta un estilo totalmente distinto de pensar, que puede llevarte a nuevas percepciones que no obtendrías sentado en tu escritorio.

No hay ninguna evidencia para esa explicación de los beneficios de caminar, pero es una idea tentadora.

Comer espaguetis

No está claro que alimentaba la extraordinaria mente de Einstein, aunque en la internet aparece la dudosa afirmación de que eran los espaguetis.

Einstein sí dijo, en broma, que sus cosas favoritas de Italia eran "los espaguetis y el matemático Levi-Civita".

En todo caso, aunque los carbohidratos tienen mala fama, el genio tenía razón.

Es sabido que el cerebro devora el 20% de la energía del cuerpo, aunque solo representa el 2% de su peso, prefiriendo azúcares simples, como la glucosa, desglosada de carbohidratos.

Derechos de autor de la imagenSCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Derechos de autor de la imagenSCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Pero a pesar de su afición a lo dulce, el cerebro no tiene forma de almacenar energía y cuando los niveles de glucosa bajan, se le acaba rápidamente.

"El cuerpo puede recurrir a su propio almacenamiento de glicógeno, liberando hormonas de estrés como el cortisol, pero eso tiene efectos colaterales", apunta Leigh Gibson, profesor de psicología y fisiología en la Universidad de Roehampton, Inglaterra.

Un estudio encontró que las personas con una dieta baja en carbohidratos tenían un tiempo de reacción más lento y memoria espacial reducida, aunque solo a corto plazo.

Pero aunque los azúcares pueden darle al cerebro un valioso impulso, desafortunadamente eso no significa que los espaguetis sean una buena idea.

"Habitualmente la evidencia sugiere que cerca de 25g de carbohidratos (37 hebras de espagueti) es algo beneficioso, pero si duplicas esa cantidad podrías en realidad perjudicar tu capacidad de pensar", señala Gibson.

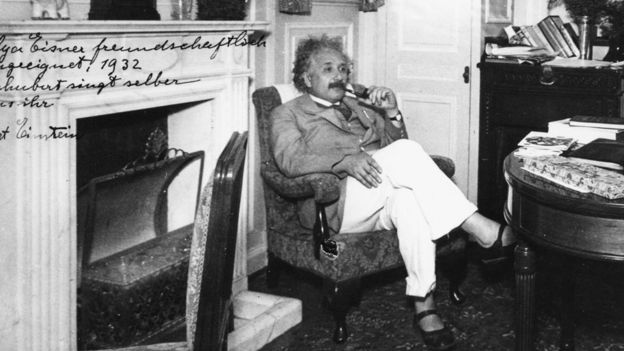

Fumar pipa

Einstein era un fumador de pipa empedernido y conocido en el campus tanto por la nube de humo que lo seguía como por sus teorías.

"Contribuye de alguna manera a un juicio calmado y objetivo en todos los asuntos humanos", dijo.

Derechos de autor de la imagenGETTY IMAGES

Derechos de autor de la imagenGETTY IMAGES

Incluso recogía las colillas de cigarrillos de la calle y les quitaba el tabaco que quedaba para ponerlo en su pipa.

No luce realmente como el comportamiento de un genio, pero en su defensa el tabaco no fue públicamente vinculado al cáncer de pulmón y otras enfermedades hasta 1962, siete años después de su muerte.

Ahora sus riesgos no son ningún secreto.

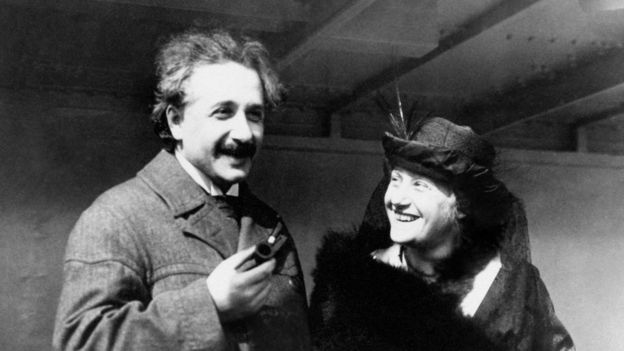

Sin medias

Ninguna lista de las excentricidades de Einstein estaría completa sin mencionar su apasionada aversión al uso de medias.

"Cuando era joven, me di cuenta que el dedo gordo siempre terminaba abriendo un hueco en la media. Así que dejé de usarlas", le escribió a Elsa, su prima y luego esposa.

Cuando era joven, me di cuenta que el dedo gordo siempre terminaba abriendo un hueco en la media. Así que dejé de usarlas"

Albert Einstein

Probablemente, esa apariencia "hipster" no le proporcionó ningún beneficio y, desafortunadamente, no ha habido ningún estudio que se ocupe del impacto de andar sin medias.

Sin embargo, el cambio a usar ropa casual, en vez de un traje más formal ha sido vinculado a un desempeño deficiente en pruebas de pensamiento abstracto.

En todo caso, qué mejor forma de terminar que con una recomendación del propio Einstein.

"Lo importante es no dejar de cuestionar. La curiosidad tiene su propia razón de existir", dijo a la revista Life en 1955.

Si eso falla, podrías intentar algunos ejercicios con los dedos de los pies. Quizás funcione.

¿Y no te mueres por averiguarlo?

興味深く読みました:

\documentclass[12pt]{article}

\usepackage{latexsym,amsmath,amssymb,amsfonts,amstext,amsthm}

\numberwithin{equation}{section}

\begin{document}

\title{\bf Announcement 179: Division by zero is clear as z/0=0 and it is fundamental in mathematics\\

}

\author{{\it Institute of Reproducing Kernels}\\

Kawauchi-cho, 5-1648-16,\\

Kiryu 376-0041, Japan\\

\date{\today}

\maketitle

{\bf Abstract: } In this announcement, we shall introduce the zero division $z/0=0$. The result is a definite one and it is fundamental in mathematics.

\bigskip

\section{Introduction}

%\label{sect1}

By a natural extension of the fractions

\begin{equation}

\frac{b}{a}

\end{equation}

for any complex numbers $a$ and $b$, we, recently, found the surprising result, for any complex number $b$

\begin{equation}

\frac{b}{0}=0,

\end{equation}

incidentally in \cite{s} by the Tikhonov regularization for the Hadamard product inversions for matrices, and we discussed their properties and gave several physical interpretations on the general fractions in \cite{kmsy} for the case of real numbers. The result is a very special case for general fractional functions in \cite{cs}.

The division by zero has a long and mysterious story over the world (see, for example, google site with division by zero) with its physical viewpoints since the document of zero in India on AD 628, however,

Sin-Ei, Takahasi (\cite{taka}) (see also \cite{kmsy}) established a simple and decisive interpretation (1.2) by analyzing some full extensions of fractions and by showing the complete characterization for the property (1.2). His result will show that our mathematics says that the result (1.2) should be accepted as a natural one:

\bigskip

{\bf Proposition. }{\it Let F be a function from ${\bf C }\times {\bf C }$ to ${\bf C }$ such that

$$

F (b, a)F (c, d)= F (bc, ad)

$$

for all

$$

a, b, c, d \in {\bf C }

$$

and

$$

F (b, a) = \frac {b}{a }, \quad a, b \in {\bf C }, a \ne 0.

$$

Then, we obtain, for any $b \in {\bf C } $

$$

F (b, 0) = 0.

$$

}

\medskip

\section{What are the fractions $ b/a$?}

For many mathematicians, the division $b/a$ will be considered as the inverse of product;

that is, the fraction

\begin{equation}

\frac{b}{a}

\end{equation}

is defined as the solution of the equation

\begin{equation}

a\cdot x= b.

\end{equation}

The idea and the equation (2.2) show that the division by zero is impossible, with a strong conclusion. Meanwhile, the problem has been a long and old question:

As a typical example of the division by zero, we shall recall the fundamental law by Newton:

\begin{equation}

F = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}

\end{equation}

for two masses $m_1, m_2$ with a distance $r$ and for a constant $G$. Of course,

\begin{equation}

\lim_{r \to +0} F =\infty,

\end{equation}

however, in our fraction

\begin{equation}

F = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{0} = 0.

\end{equation}

\medskip

Now, we shall introduce an another approach. The division $b/a$ may be defined {\bf independently of the product}. Indeed, in Japan, the division $b/a$ ; $b$ {\bf raru} $a$ ({\bf jozan}) is defined as how many $a$ exists in $b$, this idea comes from subtraction $a$ repeatedly. (Meanwhile, product comes from addition).

In Japanese language for "division", there exists such a concept independently of product.

H. Michiwaki and his 6 years old girl said for the result $ 100/0=0$ that the result is clear, from the meaning of the fractions independently the concept of product and they said:

$100/0=0$ does not mean that $100= 0 \times 0$. Meanwhile, many mathematicians had a confusion for the result.

Her understanding is reasonable and may be acceptable:

$100/2=50 \quad$ will mean that we divide 100 by 2, then each will have 50.

$100/10=10 \quad$ will mean that we divide 100 by10, then each will have 10.

$100/0=0 \quad$ will mean that we do not divide 100, and then nobody will have at all and so 0.

Furthermore, she said then the rest is 100; that is, mathematically;

$$

100 = 0\cdot 0 + 100.

$$

Now, all the mathematicians may accept the division by zero $100/0=0$ with natural feelings as a trivial one?

\medskip

For simplicity, we shall consider the numbers on non-negative real numbers. We wish to define the division (or fraction) $b/a$ following the usual procedure for its calculation, however, we have to take care for the division by zero:

The first principle, for example, for $100/2 $ we shall consider it as follows:

$$

100-2-2-2-,...,-2.

$$

How may times can we subtract $2$? At this case, it is 50 times and so, the fraction is $50$.

The second case, for example, for $3/2$ we shall consider it as follows:

$$

3 - 2 = 1

$$

and the rest (remainder) is $1$, and for the rest $1$, we multiple $10$,

then we consider similarly as follows:

$$

10-2-2-2-2-2=0.

$$

Therefore $10/2=5$ and so we define as follows:

$$

\frac{3}{2} =1 + 0.5 = 1.5.

$$

By these procedures, for $a \ne 0$ we can define the fraction $b/a$, usually. Here we do not need the concept of product. Except the zero division, all the results for fractions are valid and accepted.

Now, we shall consider the zero division, for example, $100/0$. Since

$$

100 - 0 = 100,

$$

that is, by the subtraction $100 - 0$, 100 does not decrease, so we can not say we subtract any from $100$. Therefore, the subtract number should be understood as zero; that is,

$$

\frac{100}{0} = 0.

$$

We can understand this: the division by $0$ means that it does not divide $100$ and so, the result is $0$.

Similarly, we can see that

$$

\frac{0}{0} =0.

$$

As a conclusion, we should define the zero divison as, for any $b$

$$

\frac{b}{0} =0.

$$

See \cite{kmsy} for the details.

\medskip

\section{In complex analysis}

We thus should consider, for any complex number $b$, as (1.2);

that is, for the mapping

\begin{equation}

w = \frac{1}{z},

\end{equation}

the image of $z=0$ is $w=0$. This fact seems to be a curious one in connection with our well-established popular image for the point at infinity on the Riemann sphere.

However, we shall recall the elementary function

\begin{equation}

W(z) = \exp \frac{1}{z}

\end{equation}

$$

= 1 + \frac{1}{1! z} + \frac{1}{2! z^2} + \frac{1}{3! z^3} + \cdot \cdot \cdot .

$$

The function has an essential singularity around the origin. When we consider (1.2), meanwhile, surprisingly enough, we have:

\begin{equation}

W(0) = 1.

\end{equation}

{\bf The point at infinity is not a number} and so we will not be able to consider the function (3.2) at the zero point $z = 0$, meanwhile, we can consider the value $1$ as in (3.3) at the zero point $z = 0$. How do we consider these situations?

In the famous standard textbook on Complex Analysis, L. V. Ahlfors (\cite{ahlfors}) introduced the point at infinity as a number and the Riemann sphere model as well known, however, our interpretation will be suitable as a number. We will not be able to accept the point at infinity as a number.

As a typical result, we can derive the surprising result: {\it At an isolated singular point of an analytic function, it takes a definite value }{\bf with a natural meaning.} As the important applications for this result, the extension formula of functions with analytic parameters may be obtained and singular integrals may be interpretated with the division by zero, naturally (\cite{msty}).

\bigskip

\section{Conclusion}

The division by zero $b/0=0$ is possible and the result is naturally determined, uniquely.

The result does not contradict with the present mathematics - however, in complex analysis, we need only to change a little presentation for the pole; not essentially, because we did not consider the division by zero, essentially.

The common understanding that the division by zero is impossible should be changed with many text books and mathematical science books. The definition of the fractions may be introduced by {\it the method of Michiwaki} in the elementary school, even.

Should we teach the beautiful fact, widely?:

For the elementary graph of the fundamental function

$$

y = f(x) = \frac{1}{x},

$$

$$

f(0) = 0.

$$

The result is applicable widely and will give a new understanding for the universe ({\bf Announcement 166}).

\medskip

If the division by zero $b/0=0$ is not introduced, then it seems that mathematics is incomplete in a sense, and by the intoduction of the division by zero, mathematics will become complete in a sense and perfectly beautiful.

\bigskip

section{Remarks}

For the procedure of the developing of the division by zero and for some general ideas on the division by zero, we presented the following announcements in Japanese:

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 148} (2014.2.12): $100/0=0, 0/0=0$ -- by a natural extension of fractions -- A wish of the God

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 154} (2014.4.22): A new world: division by zero, a curious world, a new idea

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 157} (2014.5.8): We wish to know the idea of the God for the division by zero; why the infinity and zero point are coincident?

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 161} (2014.5.30): Learning from the division by zero, sprits of mathematics and of looking for the truth

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 163} (2014.6.17): The division by zero, an extremely pleasant mathematics - shall we look for the pleasant division by zero: a proposal for a fun club looking for the division by zero.

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 166} (2014.6.29): New general ideas for the universe from the viewpoint of the division by zero

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 171} (2014.7.30): The meanings of product and division -- The division by zero is trivial from the own sense of the division independently of the concept of product

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 176} (2014.8.9): Should be changed the education of the division by zero

\bigskip

\bibliographystyle{plain}

\begin{thebibliography}{10}

\bibitem{ahlfors}

L. V. Ahlfors, Complex Analysis, McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1966.

\bibitem{cs}

L. P. Castro and S.Saitoh, Fractional functions and their representations, Complex Anal. Oper. Theory {\bf7} (2013), no. 4, 1049-1063.

\bibitem{kmsy}

S. Koshiba, H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh and M. Yamane,

An interpretation of the division by zero z/0=0 without the concept of product

(note).

\bibitem{kmsy}

M. Kuroda, H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh, and M. Yamane,

New meanings of the division by zero and interpretations on $100/0=0$ and on $0/0=0$,

Int. J. Appl. Math. Vol. 27, No 2 (2014), pp. 191-198, DOI: 10.12732/ijam.v27i2.9.

\bibitem{msty}

H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh, M. Takagi and M. Yamada,

A new concept for the point at infinity and the division by zero z/0=0

(note).

\bibitem{s}

S. Saitoh, Generalized inversions of Hadamard and tensor products for matrices, Advances in Linear Algebra \& Matrix Theory. Vol.4 No.2 (2014), 87-95. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ALAMT/

\bibitem{taka}

S.-E. Takahasi,

{On the identities $100/0=0$ and $ 0/0=0$}

(note).

\bibitem{ttk}

S.-E. Takahasi, M. Tsukada and Y. Kobayashi, Classification of continuous fractional binary operators on the real and complex fields. (submitted)

\end{thebibliography}

\end{document}

For the procedure of the developing of the division by zero and for some general ideas on the division by zero, we presented the following announcements in Japanese:

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 148} (2014.2.12): $100/0=0, 0/0=0$ -- by a natural extension of fractions -- A wish of the God

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 154} (2014.4.22): A new world: division by zero, a curious world, a new idea

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 157} (2014.5.8): We wish to know the idea of the God for the division by zero; why the infinity and zero point are coincident?

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 161} (2014.5.30): Learning from the division by zero, sprits of mathematics and of looking for the truth

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 163} (2014.6.17): The division by zero, an extremely pleasant mathematics - shall we look for the pleasant division by zero: a proposal for a fun club looking for the division by zero.

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 166} (2014.6.29): New general ideas for the universe from the viewpoint of the division by zero

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 171} (2014.7.30): The meanings of product and division -- The division by zero is trivial from the own sense of the division independently of the concept of product

\medskip

{\bf Announcement 176} (2014.8.9): Should be changed the education of the division by zero

\bigskip

\bibliographystyle{plain}

\begin{thebibliography}{10}

\bibitem{ahlfors}

L. V. Ahlfors, Complex Analysis, McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1966.

\bibitem{cs}

L. P. Castro and S.Saitoh, Fractional functions and their representations, Complex Anal. Oper. Theory {\bf7} (2013), no. 4, 1049-1063.

\bibitem{kmsy}

S. Koshiba, H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh and M. Yamane,

An interpretation of the division by zero z/0=0 without the concept of product

(note).

\bibitem{kmsy}

M. Kuroda, H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh, and M. Yamane,

New meanings of the division by zero and interpretations on $100/0=0$ and on $0/0=0$,

Int. J. Appl. Math. Vol. 27, No 2 (2014), pp. 191-198, DOI: 10.12732/ijam.v27i2.9.

\bibitem{msty}

H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh, M. Takagi and M. Yamada,

A new concept for the point at infinity and the division by zero z/0=0

(note).

\bibitem{s}

S. Saitoh, Generalized inversions of Hadamard and tensor products for matrices, Advances in Linear Algebra \& Matrix Theory. Vol.4 No.2 (2014), 87-95. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ALAMT/

\bibitem{taka}

S.-E. Takahasi,

{On the identities $100/0=0$ and $ 0/0=0$}

(note).

\bibitem{ttk}

S.-E. Takahasi, M. Tsukada and Y. Kobayashi, Classification of continuous fractional binary operators on the real and complex fields. (submitted)

\end{thebibliography}

\end{document}

Title page of Leonhard Euler, Vollständige Anleitung zur Algebra, Vol. 1 (edition of 1771, first published in 1770), and p. 34 from Article 83, where Euler explains why a number divided by zero gives infinity.

私は数学を信じない。 アルバート・アインシュタイン / I don't believe in mathematics. Albert Einstein→ゼロ除算ができなかったからではないでしょうか。

1423793753.460.341866474681。

Einstein's Only Mistake: Division by Zero

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿