The Bakhshali Manuscripts, a collection of 70 odd leaves of birch bark, containing a wealth of mathematical methods, have finally been dated.

The Bakhshali Manuscripts, a collection of 70 odd leaves of birch bark, containing a wealth of mathematical methods, have finally been dated. The oldest of the three samples tested was written as early as the 3rd-4th century , placing it almost five centuries earlier than where most scholars had placed the manuscripts . This makes the Bakhshali Manuscripts the oldest recorded use of a large dot, the precursor of our current form of zero. The other two fragments were dated as late 8th, and 10th century compositions, a gap of five to six centuries between the earliest one. They were clearly not written at the same time, though it is possible that the later leaves were merely copies of earlier compositions.

The manuscripts were with the Bodelian library in Oxford, who had till now refused to carbon date them, as they were deemed to be too fragile. Finally, the Library and the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit collaborate, providing a definitive answer regrading the age of the manuscript.

The manuscripts were discovered in 1881 in a village called Bakhshali, 80 kilometres from Peshawar, then British India and now Pakistan. The manuscripts were written in the Sarada script and uses a language varian that is a mixture of Sanskrit, and Prakrit of the then Gandhara region. Bakhshali was a part of the Gandhara region, in which Peshawar and Taxila were important centres. Gandhara, while a part of South Asia, had influences from Greece, Persia and China. While the Indian media has called decided that the Bakhshali manuscripts are “Indian”, the reality is that we cannot project current national identities to the past. They are the joint heritage of the region as a whole. Otherwise, the Bakhshali manuscripts would belong to Pakistan, and not India, however anti-national it may sound!

Without this dating, most of the historians of mathematics had placed it between 8th to 12th century. While the carbon dating may have solved this particular problem, it has created many new ones: which leaves are older and which were written later? Which of the mathematics dates back to 3rd- 4th century, which are post 5th-7th century, when we have a decisive break in Indian mathematics? Why did the Bakhshali manuscript have such a collection of leaves from different centuries, was it simply a collection used for training Buddhist merchants some arithmetic for their trade? If some of the leaves were created five-six centuries later than the earlier ones, did they simply copy earlier manuscripts, or did they also incorporate later advances?

In history, as in any other discipline, an answer to a given problem, quite often opens up many more questions. Bakhshali manuscripts now become even more important, as we have huge gap between the earlier period – the sulbasutras which were composed a good thousand years before Aryabhata, and the flowering of Indian mathematics.

What this dating establishes, is that the oldest recorded use of a large dot as a symbol for zero is in Bakhshali manuscripts. It is this dot notation of the zero that travelled from India into Cambodia and Indonesia, and was adopted along with other Indian numerals by the Arabs. It is this dot that later becomes the modern symbol of zero. Before the carbon dating of Bakhshali manuscripts, an inscription found in Cambodia in Old Khmer containing this symbol and dating back to the year 683 was thought to be the earliest recorded zero .

The use of the dot was in the sense we use zero today, it was used as a placeholder denoting the absence of a number. In the familiar place value notation – hundreds, tens, ones (HTO) taught in the primary schools – the dot made it easy to know that there was no digit between 1 and 9 in that place. Unlike the Roman numerals, which has a symbol for every number, the place value notation initially used only 9 symbols, with their position or place to denote multiples of tens. Hence the need for a symbol showing the absence of a number in that place.

The Bakhshali manuscripts show the use of place value notation including the use of the zero symbol. In this, it is not different from what existed earlier in Babylon and Meso America, both of which had place value notation and a symbol for an absence of a number. It existed in Babylon by 2000 BCE or four thousand years back, and was also found in Mayan texts in Meso Americas , again hundred of years before the Bakhshali manuscripts. They just used different symbols.

While it is of historical interest to know that the currently used symbol of zero originates from the South Asian region, it is by not a surprising result, considering that it is the South Asian or Indian numerals that are the basis of the modern numerals.

There is a lot of triumphalism in the media regarding the “discovery” of zero by India and how the Bakhshali manuscripts proves the Indians knew the use of zero from 3rd-- 4th century. These accounts confuse the use of zero as a symbol indicating the absence of number, and the use of zero as a number with which we can do arithmetic operations. The use of zero as a number came a few centirues later. The Bakhshali manuscripts establishes that the use of the current form of the symbol of zero, as a placeholder for an absence of a number, was prevalent in South Asia, travelling to different parts of the world from here.

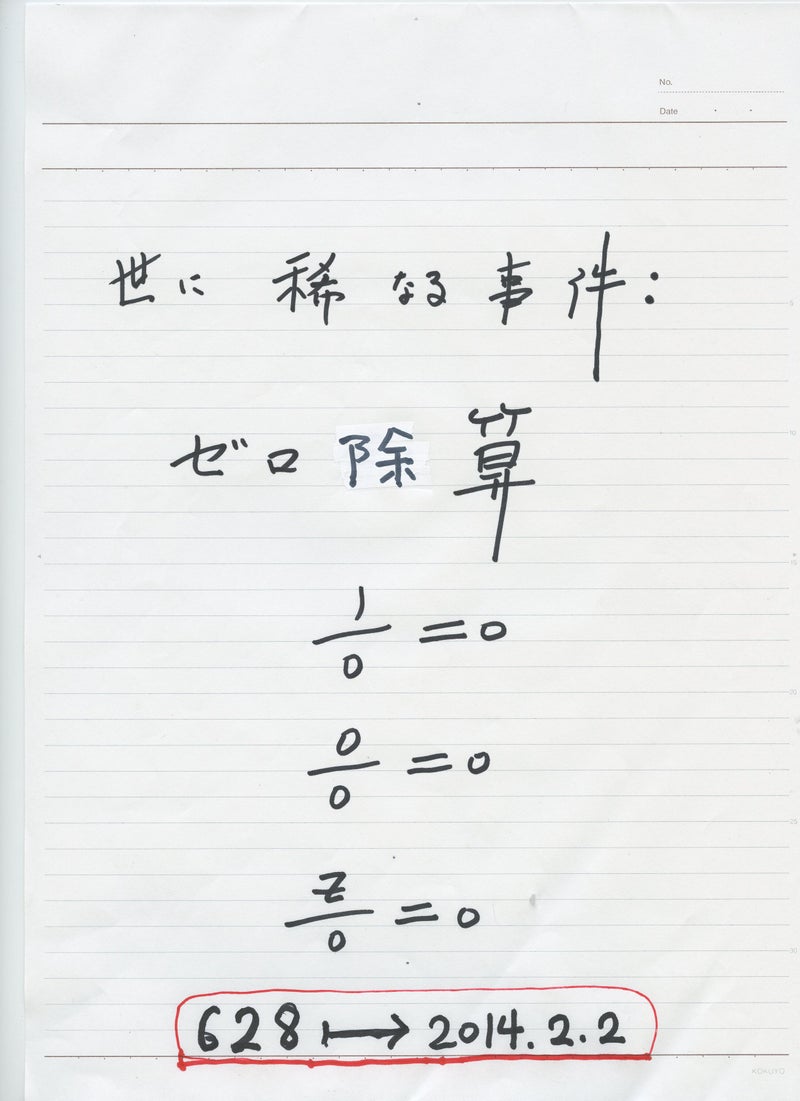

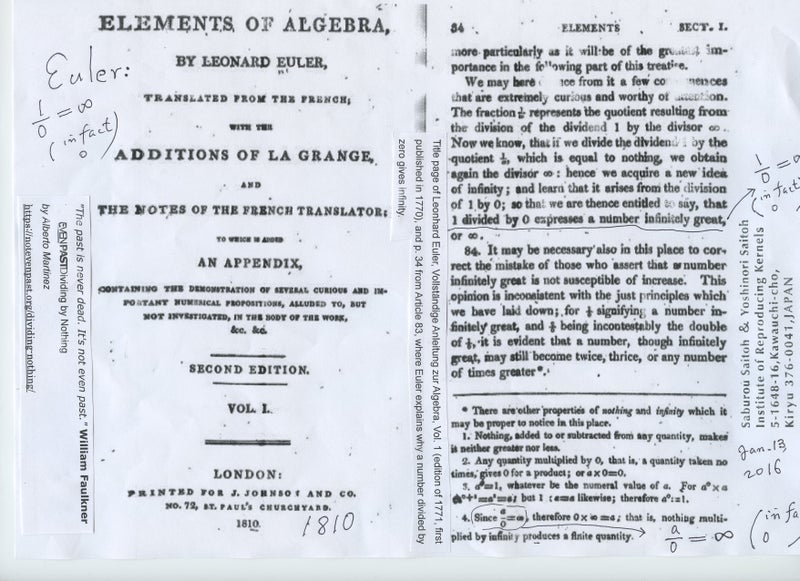

In Bakhshali manuscripts, the zero is still only a placeholder. It does not have the meaning of also being a number, with which we can do arithmetic operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication. Bramhagupta's Bramha-sputa-sidhanta, written in the 7th century is the first recorded formulation of the rules of arithmetic with zero . Brahmagupta however stumbles on the tricky issue of division by zero, defining it to be the same as multiplying by zero. Bhaskara II in the 12th century, suggested that the result of any number divided by zero is infinity , a formulation that was accepted by mathematicians for the next seven centuries. Even great mathematicians of the 18th century, such as Euler, accepted that any number divided by zero was infinity. It is only when mathematics was put on a systematic logical basis at the end of the 19th century that the “problem” of division by zero was finally “solved” – it was declared illegal, or an undefined operation!

The unique contribution of the South Asian region is not creating the modern symbol of zero, but the use of zero as a number with which we can do arithmetic operations. This is the decisive break in mathematics. It brings is zero into the family of numbers, not merely as an absence of a number but also member which it is also possible to treat as a member, though somewhat unusual one. It opened mathematics to negative numbers, indeed the entire domain of negative mathematics. Negative numbers made a number of leading mathematicians deeply unhappy as late as 18th century. Descartes and Pascal both denied negative numbers could exist. Philosophically, they could not accept negative numbers, as negative quantities – e.g., minus three apples – do not exist in nature. They were only accepted grudgingly as a useful mathematical device.

In the history of mathematics, there is also lessons to be learned on how not to deal with knowledge. Fibonacci, who had extensive contact with Arab merchants, was the first to popularise the indian-Arab numerals in Italy in the 12th century. It made accounting, a major task for the merchants, much more easy. A number of cities in Italy banned these “foreign” invasion of numbers, delaying the growth of science and mathematics in Europe. It was only after the introduction of the printing press that the Indian-Arab numerals became widely used. This history is a warning to the current dispensation, who would, like medieval Italian towns, erase foreign invasions from Indian history.

It is Brahmagupta's rules of arithmetic, followed by Mahavira's and Bhaskara that created the foundation for the modern number system. It starts by adding negative numbers, and later, imaginary numbers into the number system. Mathematics thereby was stepping beyond what are simple reflections of quantities in nature, and creating its own universe. The power of this universe is that it feeds back into science, enhancing further our understanding of nature. Without the mathematical universe and the tools it supplied for the sciences, the great advances in science would not have been possible. This is the power of the zero, not a simple sunya or an absence, but a number in its own right.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author's personal views, and do not necessarily represent the views of Newsclick.https://www.newsclick.in/dating-bakhshali-manuscripts-answering-important-questions-history-mathematics

とても興味深く読みました:

\documentclass[12pt]{article}

\usepackage{latexsym,amsmath,amssymb,amsfonts,amstext,amsthm}

\numberwithin{equation}{section}

\begin{document}

\title{\bf Announcement 380: What is the zero?\\

(2017.8.21)}

\author{{\it Institute of Reproducing Kernels}\\

Kawauchi-cho, 5-1648-16,\\

Kiryu 376-0041, Japan\\

}

\date{\today}

\maketitle

\section{What is the zero?}

The zero $0$ as the complex number or real number is given clearly by the axions by the complex number field and real number field.

For this fundamental idea, we should consider the {\bf Yamada field} containing the division by zero. The Yamada field and the division by zero calculus will arrange our mathematics, beautifully and completely; this will be our natural and complete mathematics.

\medskip

\section{ Double natures of the zero $z=0$}

The zero point $z=0$ represents the double natures; one is the origin at the starting point and another one is a representation of the point at infinity. One typical and simple example is given by $e^0 = 1,0$, two values. {\bf God loves two}.

\section{Standard value}

\medskip

The zero is a center and stand point (or bases, a standard value) of the coordinates - here we will consider our situation on the complex or real 2 dimensional spaces. By stereographic

projection mapping or the Yamada field, the point at infinity $1/0$ is represented by zero. The origin of the coordinates and the point at infinity correspond each other.

As the standard value, for the point $\omega_n = \exp \left(\frac{\pi}{n}i\right)$ on the unit circle $|z|=1$ on the complex $z$-plane is, for $n = 0$:

\begin{equation}

\omega_0 = \exp \left(\frac{\pi}{0}i\right)=1, \quad \frac{\pi}{0} =0.

\end{equation}

For the mean value

$$

M_n = \frac{x_1 + x_2 +... + x_n}{n},

$$

we have

$$

M_0 = 0 = \frac{0}{0}.

$$

\medskip

\section{ Fruitful world}

\medskip

For example, for very and very general partial differential equations, if the coefficients or terms are zero, then we have some simple differential equations and the extreme case is all the terms are zero; that is, we have trivial equations $0=0$; then its solution is zero. When we consider the converse, we see that the zero world is a fruitful one and it means some vanishing world. Recall Yamane phenomena (\cite{kmsy}), the vanishing result is very simple zero, however, it is the result from some fruitful world. Sometimes, zero means void or nothing world, however, it will show {\bf some changes} as in the Yamane phenomena.

\section{From $0$ to $0$; $0$ means all and all are $0$}

\medskip

As we see from our life figure (\cite{osm}), a story starts from the zero and ends with the zero. This will mean that $0$ means all and all are $0$. The zero is a {\bf mother} or an {\bf origin} of all.

\medskip

\section{ Impossibility}

\medskip

As the solution of the simplest equation

\begin{equation}

ax =b

\end{equation}

we have $x=0$ for $a=0, b\ne 0$ as the standard value, or the Moore-Penrose generalized inverse. This will mean in a sense, the solution does not exist; to solve the equation (6.1) is impossible.

We saw for different parallel lines or different parallel planes, their common points are the origin. Certainly they have the common points of the point at infinity and the point at infinity is represented by zero. However, we can understand also that they have no solutions, no common points, because the point at infinity is an ideal point.

Of course. we can consider the equation (6.1) even the case $a=b=0$ and then we have the solution $x=0$ as we stated.

We will consider the simple differential equation

\begin{equation}

m\frac{d^2x}{dt^2} =0, m\frac{d^2y}{dt^2} =-mg

\end{equation}

with the initial conditions, at $t =0$

\begin{equation}

\frac{dx}{dt} = v_0 \cos \alpha , \frac{d^2x}{dt^2} = \frac{d^2y}{dt^2}=0.

\end{equation}

Then, the highest high $h$, arriving time $t$, the distance $d$ from the starting point at the origin to the point $y(2t) =0$ are given by

\begin{equation}

h = \frac{v_0 \sin^2 \alpha}{2g}, d= \frac{v_0\sin \alpha}{g}

\end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}

t= \frac{v_0 \sin \alpha}{g}.

\end{equation}

For the case $g=0$, we have $h=d =t=0$. We considered the case that they are the infinity; however, our mathematics means zero, which shows impossibility.

These phenomena were looked many cases on the universe; it seems that {\bf God does not like the infinity}.

\bibliographystyle{plain}

\begin{thebibliography}{10}

\bibitem{kmsy}

M. Kuroda, H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh, and M. Yamane,

New meanings of the division by zero and interpretations on $100/0=0$ and on $0/0=0$,

Int. J. Appl. Math. {\bf 27} (2014), no 2, pp. 191-198, DOI: 10.12732/ijam.v27i2.9.

\bibitem{msy}

H. Michiwaki, S. Saitoh, and M.Yamada,

Reality of the division by zero $z/0=0$. IJAPM International J. of Applied Physics and Math. {\bf 6}(2015), 1--8. http://www.ijapm.org/show-63-504-1.html

\bibitem{ms}

T. Matsuura and S. Saitoh,

Matrices and division by zero $z/0=0$, Advances in Linear Algebra

\& Matrix Theory, 6 (2016), 51-58. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/alamt.2016.62007 http://www.scirp.org/journal/alamt

\bibitem{mos}

H. Michiwaki, H. Okumura, and S. Saitoh,

Division by Zero $z/0 = 0$ in Euclidean Spaces.

International Journal of Mathematics and Computation Vol. 28(2017); Issue 1, 2017), 1-16.

\bibitem{osm}

H. Okumura, S. Saitoh and T. Matsuura, Relations of $0$ and $\infty$,

Journal of Technology and Social Science (JTSS), 1(2017), 70-77.

\bibitem{romig}

H. G. Romig, Discussions: Early History of Division by Zero,

American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 31, No. 8. (Oct., 1924), pp. 387-389.

\bibitem{s}

S. Saitoh, Generalized inversions of Hadamard and tensor products for matrices, Advances in Linear Algebra \& Matrix Theory. {\bf 4} (2014), no. 2, 87--95. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ALAMT/

\bibitem{s16}

S. Saitoh, A reproducing kernel theory with some general applications,

Qian,T./Rodino,L.(eds.): Mathematical Analysis, Probability and Applications - Plenary Lectures: Isaac 2015, Macau, China, Springer Proceedings in Mathematics and Statistics, {\bf 177}(2016), 151-182 (Springer).

\bibitem{ttk}

S.-E. Takahasi, M. Tsukada and Y. Kobayashi, Classification of continuous fractional binary operations on the real and complex fields, Tokyo Journal of Mathematics, {\bf 38}(2015), no. 2, 369-380.

\bibitem{ann179}

Announcement 179 (2014.8.30): Division by zero is clear as z/0=0 and it is fundamental in mathematics.

\bibitem{ann185}

Announcement 185 (2014.10.22): The importance of the division by zero $z/0=0$.

\bibitem{ann237}

Announcement 237 (2015.6.18): A reality of the division by zero $z/0=0$ by geometrical optics.

\bibitem{ann246}

Announcement 246 (2015.9.17): An interpretation of the division by zero $1/0=0$ by the gradients of lines.

\bibitem{ann247}

Announcement 247 (2015.9.22): The gradient of y-axis is zero and $\tan (\pi/2) =0$ by the division by zero $1/0=0$.

\bibitem{ann250}

Announcement 250 (2015.10.20): What are numbers? - the Yamada field containing the division by zero $z/0=0$.

\bibitem{ann252}

Announcement 252 (2015.11.1): Circles and

curvature - an interpretation by Mr.

Hiroshi Michiwaki of the division by

zero $r/0 = 0$.

\bibitem{ann281}

Announcement 281 (2016.2.1): The importance of the division by zero $z/0=0$.

\bibitem{ann282}

Announcement 282 (2016.2.2): The Division by Zero $z/0=0$ on the Second Birthday.

\bibitem{ann293}

Announcement 293 (2016.3.27): Parallel lines on the Euclidean plane from the viewpoint of division by zero 1/0=0.

\bibitem{ann300}

Announcement 300 (2016.05.22): New challenges on the division by zero z/0=0.

\bibitem{ann326}

Announcement 326 (2016.10.17): The division by zero z/0=0 - its impact to human beings through education and research.

\bibitem{ann352}

Announcement 352(2017.2.2): On the third birthday of the division by zero z/0=0.

\bibitem{ann354}

Announcement 354(2017.2.8): What are $n = 2,1,0$ regular polygons inscribed in a disc? -- relations of $0$ and infinity.

\bibitem{362}

Announcement 362(2017.5.5): Discovery of the division by zero as

$0/0=1/0=z/0=0$.

\end{thebibliography}

\end{document}

The division by zero is uniquely and reasonably determined as 1/0=0/0=z/0=0 in the natural extensions of fractions. We have to change our basic ideas for our space and world

Division by Zero z/0 = 0 in Euclidean Spaces

Hiroshi Michiwaki, Hiroshi Okumura and Saburou Saitoh

International Journal of Mathematics and Computation Vol. 28(2017); Issue 1, 2017), 1

-16.

http://www.scirp.org/journal/alamt http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/alamt.2016.62007

http://www.ijapm.org/show-63-504-1.html

http://www.diogenes.bg/ijam/contents/2014-27-2/9/9.pdf

http://okmr.yamatoblog.net/division%20by%20zero/announcement%20326-%20the%20divi

http://okmr.yamatoblog.net/

Relations of 0 and infinity

Hiroshi Okumura, Saburou Saitoh and Tsutomu Matsuura:

http://www.e-jikei.org/…/Camera%20ready%20manuscript_JTSS_A…

https://sites.google.com/site/sandrapinelas/icddea-2017

2017.8.21.06:37

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿